Human reproduction is notoriously inefficient. Whereas the fertilized eggs of other animals, such as mice, usually progress to more complex embryo stages, fertilized human eggs often falter early on. For a recent study in Genome Medicine, scientists analyzed almost 1,000 embryos from in vitro fertilization (IVF) procedures to learn why.

Scientists know that chromosomally abnormal human embryos—those with either more or fewer than 46 chromosomes—often don't implant in the uterus, and if they do, the resulting pregnancy may end in a miscarriage or stillbirth.

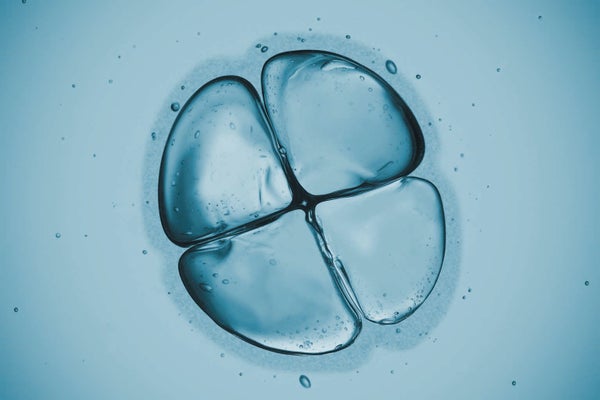

Some of these abnormalities originate in the egg or sperm. In other cases, a healthy egg and sperm form an embryo that divides oddly; for example, instead of one cell dividing into two, it might become three. “There is a lot of evidence that during the first cell divisions, human embryos make a lot of mistakes,” says Claudia Spits, who studies related problems of reproduction and genetics at the Free University of Brussels.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The study authors found that these odd divisions lead to new chromosomal abnormalities, which can harm embryonic development even more than abnormalities that originate in the egg or sperm. The new errors can be “catastrophic,” says Johns Hopkins University evolutionary biologist Rajiv McCoy, the study's lead author. “A lot of times you have three, four, five missing chromosomes.”

McCoy and his colleagues used time-lapse video and a microscope to record the IVF embryos' first cell divisions. Then they tested for abnormalities among both the surviving embryos and those that failed.

Spits says the effects of postfertilization abnormalities are “something that we have all assumed to be true, but nobody provided the evidence in the manner that [McCoy and his team] have done” by analyzing such a high number of embryos and including discarded ones.

The new study also found that division-related errors are equally common among embryos with eggs from women of all ages, whereas egg and sperm abnormalities increase as people age. The researchers suspect this finding might help explain why it is so hard even for many young, healthy couples to get pregnant. “Maybe some of the mechanisms that we are uncovering from our studies will be relevant to understanding the low level of human fertility,” says study co-author Michael Summers, a reproductive medicine consultant at London Women's Clinic. The work could also help illuminate what McCoy calls “the black box of early pregnancy loss.”

The scientists say they hope to use their results to improve IVF. For instance, if changing the cells' environment reduces the likelihood of dividing errors, Summers says, “you could potentially rescue a lot of embryos for IVF purposes because those errors are happening in the dish.”