Both anti-Jewish and anti-Muslim hate is on the rise in the U.S. Just two weeks after the start of the conflict in Israel and Palestine, hate incidents grew by 400 percent against Jews, and increased by 216 percent over a four-week period against Muslims, compared to the previous year.

Antisemitic and Islamophobic hate is surging most dramatically online. A recent New York Times article reported that online hate has spiked on mainstream social media platforms like X (formerly Twitter), Facebook and Instagram, with most of the hateful antisemitic and Islamophobic content appearing on X. Far-right users of Telegram and 4chan have been leveraging the current conflict, the report noted, as an opportunity to spread antisemitic and Islamophobic rhetoric.

This is not for the first time. Muslims and Jews face enormously high rates of online and physical-world hate, and a deep connection links that hate in the U.S. We only have to look at the last decade to see it.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

In a recent paper published in Political Behavior, we looked at anti-Muslim and anti-Jewish online and offline hate—both before and after the 2016 U.S. presidential election—evaluating their relationship from 2015 to 2018.

Hate speech then flowed freely. Throughout the 2016 presidential campaign, candidates (including, but not limited to, then-candidate Donald Trump) openly engaged in inflammatory rhetoric, often targeting Muslim communities. Extremist white nationalist rhetoric also became more explicit and commonplace. Contemporaneously, offline hate crimes soared against minority communities, particularly against Jews and Muslims. This was never more apparent than following the start of the Trump presidency, when in 2017, antisemitic incidents saw their largest single-year increase on record, at nearly 60 percent higher than in 2016, and Islamophobic abuse rose 91 percent in the first half of 2017. All of this appeared to come to a head in August 2017 at the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Va., which marked a significant escalation in public, organized, far-right extremist activity in the U.S.

Our research triangulated across multiple databases to examine hate against Muslims and Jews on fringe platforms online and in its real-world manifestations. We included discussions held on 4chan, Gab and Reddit, both fringe and mainstream, as well as hate crime databases maintained by the Anti-Defamation League, Council on American Islamic Relations and the FBI, in the analysis.

Our findings revealed surprising insights. Overall, anti-Muslim and anti-Jewish hate crimes might appear to be more disconnected than they are in reality. That’s because increases in hate crimes against the two groups often (though not always) occur at different times. However, this appears to happen because, perhaps counterintuitively, attacks come from the same fringe hate communities—ones whose members seem to coordinate attacks on one group or the other based on whichever one they can most easily link to ongoing events. In other words, and as one might expect, hate groups do not see ebbs and flows in hate—but they do regularly alter which communities they target and why they say they are targeting them.

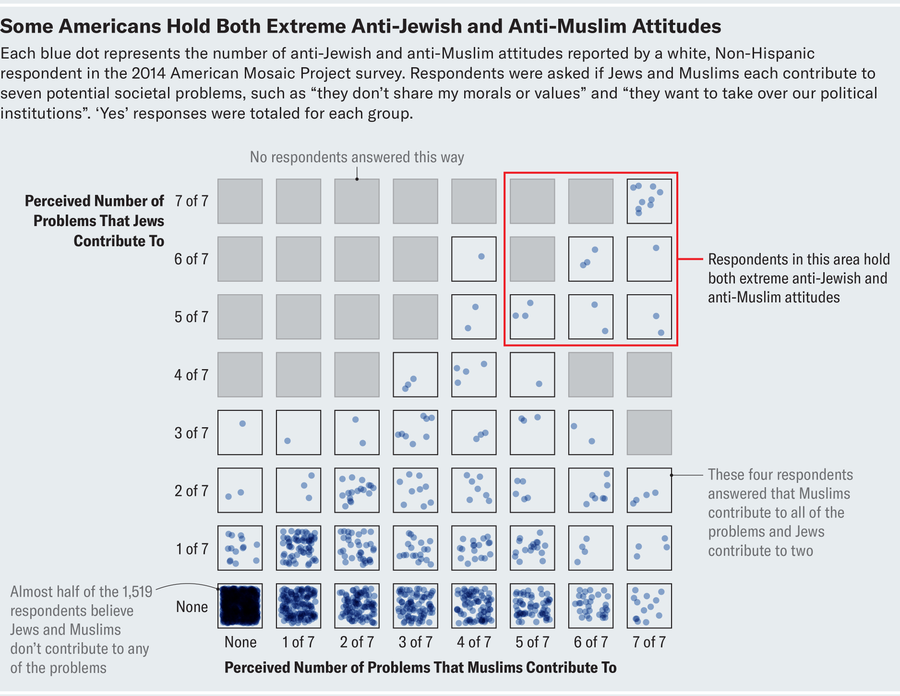

University of Minnesota researchers have already shown that clusters of Americans hold both extreme anti-Jewish and anti-Muslim attitudes. We replicated this finding through survey data, shown below. However, we also found these attitudes manifest against each group—in online hate speech and offline hate crimes—at different times.

Looking at online hate speech for example, when White nationalism was on the rise in 2017, anti-Muslim hate speech declined one month before the Unite the Right rally. Despite this, overall hate remained essentially constant within online fringe communities, as shown in the figure below. When anti-Muslim hate speech declined on these platforms, anti-Jewish hate replaced it. As seen in the right panel of that chart, we found changes in mentions of Jews and Muslims/Arabs on Gab, an extremist social networking site, that contained predicted hate speech compared to January 2017 among its users who posted every month from January 2017 through August 2018. Although more difficult for us to study than these aggregate shifts, additional analyses on Gab suggest that hate speech against Muslims was substituted by the same far-right users who espoused hate speech against Jews.

Credit: William Hobbs, restyled by John Knight; Source: “From Anti-Muslim to Anti-Jewish: Target Substitution on Fringe Social Media Platforms and the Persistence of Online and Offline Hate,” by William Hobbs et al., in Political Behavior; September 7, 2023

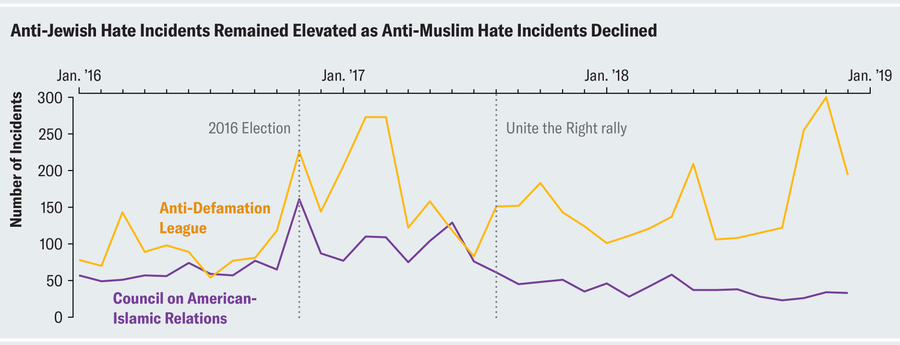

We also examine patterns in offline hate. The number of offline anti-Jewish hate incidents reported to the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), as well as the number of anti-Muslim ones reported to the Council on American Islamic Relations (CAIR), are shown below in the last chart. Noticeable is the increase in both anti-Muslim and anti-Jewish hate crimes in the months after the 2016 election. Beyond this, our results indicate not only that both anti-Muslim online and offline hate receded in mid-2017 (the dashed line below, one month prior to “Unite the Right”), but also that anti-Jewish offline and online hate remained at their elevated levels (see the solid line in the panel below, around the August 2017 rally)—and, for more severe and what we term “likely to be reported” crimes, anti-Jewish hate crimes increased while anti-Muslim hate crimes declined, according to FBI data.

Credit: William Hobbs, restyled by John Knight; Source: “From Anti-Muslim to Anti-Jewish: Target Substitution on Fringe Social Media Platforms and the Persistence of Online and Offline Hate,” by William Hobbs et al., in Political Behavior; September 7, 2023

Additional analyses reveal that even week-to-week changes in online extremist speech targeting one group rather than the other (e.g., Muslims rather than Jews) predicted subsequent shifts in hate crimes and bias incidents offline against one group, rather than the other (regardless of whether we control for terror attacks and media coverage of hate crimes).

Contemporary discourse often pits Muslims and Jews against one another. But our research demonstrates that a large amount of seemingly disconnected hateful rhetoric about both—at least in 2017—originated from the same far-right extremist communities. We urge observers, researchers and leaders to investigate the traces and origins of the hate targeting both groups today, and to consider the potential outsized role that extremist communities may be playing in stoking hatred against Muslims and Jews today.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.