Columbia University glaciologist Alexandra Boghosian spent two years studying a meltwater river on Greenland’s Petermann Ice Shelf. She suspected the river ended in a waterfall like the one that cascades off the Nansen Ice Shelf in Antarctica, potentially keeping water from accumulating in melt ponds that can damage the ice. Instead Boghosian and her team discovered a new phenomenon: a deep-cut river channel that could contribute to future ice-calving events and accelerate sea-level rise.

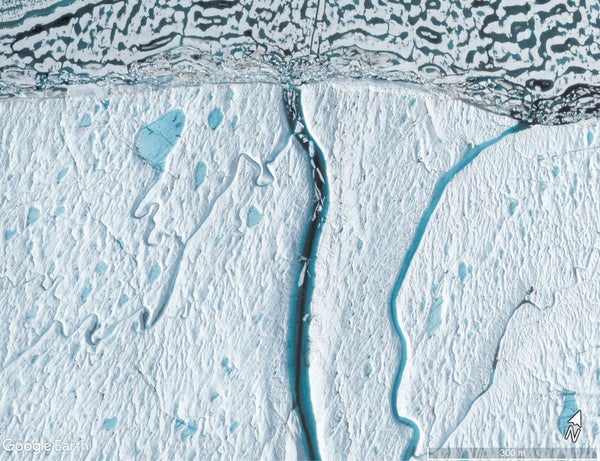

The team first spotted the phenomenon in 2018 using Google Earth; an overhead view showed sea ice floating in a river carving into the ice shelf. Further work confirmed this river had cut so deep its water actually flowed backward, from the sea up to half a mile into the channel. “We called it an ‘estuary’ because of the evidence of this flow reversal that mixes fresh and salt water,” Boghosian says. She and her colleagues detailed their find in Nature Geoscience.

The researchers also noticed ice fractures running parallel to the river along its backward-flowing section. “The type of fractures they found can really set up ice for failure because ocean water can get in there and erode them,” says Catherine Walker, a glaciologist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, who was not involved with the study. Such fractures can contribute to calving events, in which large blocks crack off a shelf. With reduced mass, shelves cannot as readily hold back advancing glaciers behind them, and more ice flows into the ocean, raising sea levels faster. Increasing temperatures from climate change could cause more of these rivers to run for longer periods with more meltwater and cut too deep.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Relatively warm water flows in “upside-down rivers” underneath some ice shelves, melting the bottom and letting surface ice settle to form depressions on top. Water flowing through such channels could also make shelves more prone to forming estuaries. “These linear features mean the river is going to form in the same place every year, allowing the water to incise deeper,” Boghosian says.

Most of the world’s ice shelves are in Antarctica and experience less meltwater than Greenland’s do, but climate change could lessen the gap. “I don’t think the volume of meltwater has been able to establish one of these estuaries in Antarctica,” Walker says, “but this study is certainly forward-looking as to what could happen to weaken those big ice shelves.”