Cancer is a deeply emotional diagnosis, so rooted in our fears that seemingly miraculous cures never fail to capture attention. In May a viral tweet for example proclaimed an ostensible medical miracle: a woman with breast cancer shirked chemotherapy to cure her cancer with a special dietary protocol. Yet while millions embraced the claim, few undertook the minimal detective work needed to ascertain that she in fact had surgery, a standard intervention for low-risk localized breast cancer. That fact was tellingly absent from the hyperbole about her cure.

Such disingenuous behavior around cancer is not uncommon, nor are such claims unique. Across TikTok, videos on cancer-curing diets garner billions of views. For Amazon and other online retailers, cancer diet books are top sellers. Online and off, snake-oil peddlers hawk miracle cancer cures not backed by any science, from alternative therapy to herbal remedies. For patients and loved ones, promises that something simple might cure or prevent cancer are understandably appealing. But far from being anticancer talismans, these purported treatments often come laden with insidious harm.

The notion that a particular diet, for example, can cause, or cure, cancer is ubiquitous but mistaken. Some foods are known carcinogens, such as alcohol and processed meat, with heavy consumption of the latter increasing absolute risk for colorectal cancer over a lifetime by approximately 1 percent. But there are no miracle diets that cure cancer, nor any particular diet responsible for it either. In Lancet Oncology last year, surgeon and cancer survivor Liz O’Riordan and I delved into the disturbing prevalence of the dietary myths surrounding cancer. Assertions that sugar or carbohydrates “feed” cancer feature prominently, giving rise to the related claim that high-protein ketogenic or all-meat diets cure cancer. At the complete opposite end of the nonsense spectrum, others insist that acidity enables cancer cells to take hold, advocating alkaline or vegan diets to stave off cancer.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

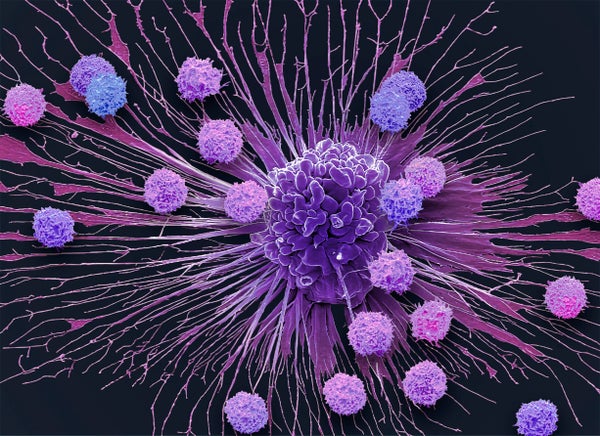

These claims are false, stemming from a glaring misunderstanding of a real phenomenon in cancer biology about how cells are fuelled. In healthy tissue, cells get energy from “aerobic” respiration, employing oxygen to produce ample amounts of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the energy source for our cells. Tumor cells, in contrast, often use far more inefficient glycolysis, which foregoes oxygen and instead uses additional glucose to yield lesser amounts of ATP. The predilection of cancer cells toward this “anaerobic” respiration is known as the Warburg effect. When German medical scientist Otto Warburg discovered it in 1924, he suggested this switch to glycolysis might drive cancer. We now know the shift stems from the mutations that lead to cancer, rendering it a consequence rather than a cause.

Dietary evangelists, however, seem to have missed the last century of cancer research. While tumor cells disproportionately consume glucose, you cannot “starve” cancer by avoiding carbohydrates. That’s because normal aerobic respiration also needs glucose—and otherwise you simply end up starving the patient. Nor does your body especially care whether the source of that initial glucose is a carrot or carrot cake. The major risk with restrictive diets in cancer is that they typically result in weight loss, potentially dangerous for patients, and unsafe without guidance from an oncology dietitian.

The same confusion lurks beneath alkaline and vegan diets for cancer. When tumor cells switch to glycolic respiration, a byproduct makes the tumor microenvironment acidic. Believers in these diets insist nonacidic foods reverse this switchover, but again this is sorely misguided. Acidity is not a cause of cancer, but a consequence. Tissue acidity can’t be changed through diet; it is tightly regulated by our bodies, a blessing that prevents spicy meals from literally killing us. And while obesity is linked to cancer, the link arises from a complex interplay of hormone signaling in fat cells and resultant inflammation, not any specific diet.

Patients bombarded with these claims are alternately shamed into thinking they “caused” their cancer, or even worse, to embrace these diets without realizing induced weight loss is often highly dangerous for them.

Cancer quackery goes far beyond food: “natural” cures for cancer abound, from homeopathy to energy-healing, all proffered without a modicum of evidence. Painless miracle cures flaunted with a high confidence and suspect testimonials hold more allure to vulnerable patients than often invasive conventional, effective treatment, which almost always comes with serious side effects.

But patients who turn to alternative and complementary treatments tend to fare worse, having a significantly higher risk of dying relative to those who did not use complementary approaches, even when all other relevant factors are considered. For some cancers, the use of complementary medicine was associated with over a doubling in the risk of death. This is likely because they often delay or refuse conventional treatment until problems become more advanced, and much more resistant to efficacious treatment. Apple’s Steve Jobs is an exemplar of this: he was diagnosed with a rare type of pancreatic cancer that is treatable with surgery if caught in time; but Jobs rejected conventional treatment, opting for juicing diets instead. By the time he conceded this was not helping, his cancer was too advanced to treat. Jobs’s death made headlines because of his fame, but similar tragedies play out daily for bereaved families worldwide.

Even more cruel, alternative cancer clinics promise miracles, operating in poorly regulated regions worldwide. With lofty promises and slick testimonials, they exploit patients for vast fortunes, commodifying false hope. Their litany of offenses is as appalling as it is extensive; some falsely declare patients cancer-free with false scans, peddle ineffective but dangerous concoctions, or use patient testimonials after the patient has died. All are utterly unconcerned with patient well-being, leaving them and their loved ones destitute.

Those pushing “natural” cures cause further harm still when they insist conventional treatment is a scam, and that a cure to cancer is suppressed by the nebulous big pharma. So prevalent is that conspiracy theory that 37 percent of Americans believe the FDA is withholding a cancer cure, despite this being virtually impossible. A single “magic bullet” to cure cancer is unrealistic, to start with, because it is not one disease, but a myriad of maladies, united only by the fact cancer cells don’t obey the rules limiting their proliferation like healthy cells.

Complex as cancer is, the real news is that survival rates improve year after year. This year has already seen some extremely promising developments in cancer vaccines, with more on the horizon. But the dark reality of the social media era is that misinformation about cancer is rife, with serious dangers for patients. While miraculous claims hold understandable appeal, our best protection against charlatans and fools is always healthy skepticism.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.