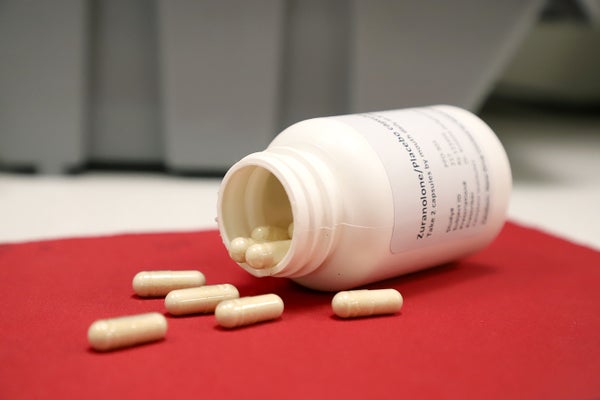

Last Friday the Food and Drug Administration approved the first oral pill specifically targeted to treat postpartum depression—the most common complication of childbirth. The new medication, known as zuranolone, works more quickly than existing antidepressant treatments for postpartum depression and is given once a day for just two weeks.

One in seven people who have given birth experience postpartum depression, but roughly half of people with the condition do not receive treatment. As mental health struggles have become the leading cause of pregnancy-related deaths in the U.S., experts emphasize the importance of expanding the arsenal of treatments for postpartum depression.

“For the first time, we have a fast-acting medication for postpartum depression that patients can conveniently take by mouth,” says Nancy Byatt, a perinatal psychiatrist at the University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School, who was not involved in developing the drug. “This is a major addition to our toolbox and will hopefully spark more conversations about the stigma new parents face when seeking mental health care.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The FDA’s decision follows a new study that demonstrated the effectiveness of a two-week course of zuranolone in reducing postpartum depression symptoms. In the placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial, nearly 200 people with severe postpartum depression were given either 50 milligrams per day of zuranolone or a placebo pill for 14 days. Symptom severity was measured using the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), which assesses the presence and intensity of symptoms, including suicidal ideation, insomnia, anxiety and weight loss.

After three days of treatment, those who received zuranolone experienced significant relief from depressive symptoms. At day 15, the treatment group showed a 29.4 percent greater improvement in depression scores, compared with the placebo group. Improvements began within three days and persisted for 45 days after treatment began, according to the study, which was published on July 26 in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

“The longer postpartum depression goes untreated, the more difficult it can be to successfully treat it to full remission. Zuranolone isn’t meant to replace existing treatment options like talk therapy, but the fact that we can see improvements within three days is important,” says Kristina M. Deligiannidis, a behavioral scientist at the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research and the study’s lead author. Deligiannidis was principal investigator of a similar trial that was published in JAMA Psychiatry in 2021. That earlier study showed that a reduced, 30-milligram dose of zuranolone also alleviates depressive symptoms through a 45-day period. The 2021 study and the recent zuranolone trial were both funded by Sage Therapeutics, the pharmaceutical company that co-developed zuranolone with Biogen.

Sage Therapeutics had also submitted zuranolone to the FDA for the treatment of major depressive disorder. But, citing limited data, the agency did not approve it for that use.

The drug’s ability to provide rapid relief makes it an especially ideal treatment for postpartum depression, according to Samantha Meltzer-Brody, director of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Center for Women’s Mood Disorders. “With postpartum depression, it’s not just the mother that’s struggling. It’s a huge stressor for the family and the baby,” she says, explaining that poor mental health in new parents is strongly associated with worse health outcomes for their newborns. Because infancy is a particularly critical developmental period, promptly treating postpartum depression is crucial to ensuring a child’s long-term health. “If we have a treatment that can act quickly and be given in a convenient way, we can decrease suffering for so many people and their families.”

Until a few years ago, clinicians treated postpartum depression with a combination of psychotherapy and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), a type of antidepressant that includes Prozac and Lexapro. But SSRIs are sluggish—it can take up to three months for people to respond to these drugs, and they may need to be taken indefinitely.

Then, in 2019, the FDA approved brexanolone as the first drug specifically for the treatment of postpartum depression. But brexanolone, which is also manufactured by Sage Therapeutics and sold under the brand name Zulresso, isn’t widely used because it costs $34,000 per dose and must be given in a hospital as an intravenous infusion for 60 hours straight.

Zuranolone is a “first cousin” of brexanolone, says Meltzer-Brody, who was principal investigator of brexanolone’s clinical trials. Both drugs mimic allopregnanolone, a naturally occurring neurosteroid that protects the brains of pregnant people and their fetuses from stress during pregnancy. The drugs target the brain’s GABA receptors—part of a major signaling pathway that is responsible for stress and mood regulation—to compensate for reduced levels of allopregnanolone in people with postpartum depression. In contrast with traditional SSRIs, zuranolone and brexanolone provide fast and sustained relief after a single course of treatment. Zuranolone has been modified so it can be ingested in a more convenient oral form, however.

Sage Therapeutics designed zuranolone to be an “episodic” treatment akin to an antibiotic regimen—that means people take the drug for two weeks and then stop. But it’s unclear how long zuranolone’s benefits persist beyond the 45-day period investigated in its clinical trials. If people’s symptoms recur, follow-up studies will be necessary to establish whether people can safely and effectively be treated with a second course of zuranolone, Deligiannidis says.

Although Deligiannidis anticipates zuranolone will be cheaper than the IV drug brexanolone, Sage Therapeutics has not yet disclosed its intended pricing for the medication. As of publication time, the company has not responded to requests for comment regarding the cost of zuranolone.

Byatt notes that low-income parents face higher risks of postpartum depression and greater barriers to receiving care, which underscores the need to make zuranolone affordable. She says that conversations about the drug’s pricing connect to larger questions about how we can build support systems for new parents who are shouldering the immense demands of childcare.

“When it comes to improving parental health care, it’s like a million-piece puzzle that includes having a rapid-acting medication for postpartum depression. But it also includes destigmatizing mental health care for new parents, increasing access to individual and group therapy and having regular follow-up appointments in the postpartum period,” Byatt says. “Zuranolone is a great piece to the puzzle. It’s not a panacea.”