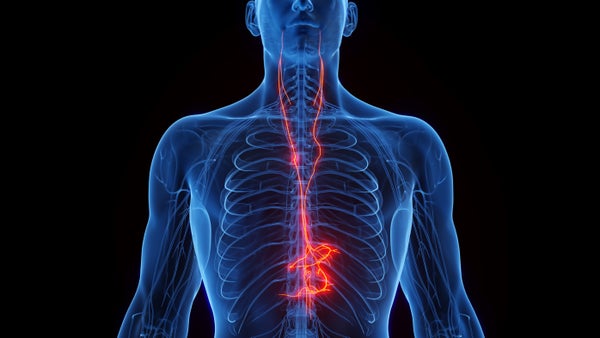

Can a condition as gnarly and disparate as long COVID be treated without drugs? Social media is buzzing over an experimental therapy that taps the vagus nerve, which acts as the body’s “information superhighway” by carrying crucial signals between the brain and various internal organs. A mild electrical zap to this long cranial nerve triggers a rush of autonomic responses associated with relaxation—and may confer health benefits well beyond this.

Researchers are increasingly recognizing that long COVID is as much a neurological disorder as a cardiovascular and respiratory one. Treatment studies have highlighted the condition’s neurological aspects, including some that are potentially related to the vagus nerve. Early small-scale trials of vagal stimulation have seen reductions in hallmark long COVID symptoms such as chronic fatigue, headaches and irregular blood pressure. Another study demonstrated that the devices used to send electrical stimulation through the skin are safe and easy to use at home—offering convenience, accessibility and less risk of contagion. Scientists are still studying which long COVID symptoms this technique can reliably address, which patients will benefit and how long the effects last. In any case, the vagus nerve’s influence throughout the body appears to be key for treating some of the all-encompassing manifestations of long COVID.

“Your body is an electrical and chemical organ,” says Peter Staats, co-chair of the Vagus Nerve Society and co-founder of the neuromodulation company electroCore. “Modern medicine has been really focused on the chemical side of things. And it's time to be focusing a little bit more on the electrical side.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Vagus nerve stimulation is already used to treat some other thorny neurological conditions. Implantable stimulators were first approved for epilepsy in 1997 and for depression in 2005. But despite the procedure’s promise for treating long COVID, researchers say it won’t be enough on its own. Long COVID is an unresolved enigma that’s tricky to understand, let alone diagnose or treat. Symptoms vary wildly between individuals, and no single approach can address the viral aftermath throughout the body. Experts say combination therapy appears best for lifting people out of this chronic condition. But vagus nerve stimulation could be a niche tool in the long COVID treatment arsenal. It has potential to address neurological symptoms in a way that limited pharmacological solutions so far have not.

“Whenever we have a single treatment option, we're generally pretty wary of saying this is going to be the cure-all,” says Stephanie Grach, an internist at the Mayo Clinic. But “at this point, almost any sort of management or treatment option that could feasibly help a number of people is a game changer.”

Stress Buster

The vagus nerve—a bundle of fibers that run from the brain stem and fan out around the body—is the impresario of our involuntary background processes and organ functions. It’s also part of the parasympathetic nervous system, which is in charge of calming the body after a stressful event. During this recovery phase, the heart rate slows to normal, the immune system lets down its guard, and the digestive system starts up again. The vagus nerve acts as an “off” switch to the sympathetic system’s fight-or-flight mode. This nerve is also activated during activities such as yoga, meditation and slow breathing, all of which commonly leave practitioners feeling calm and restful.

Electrical stimulation harnesses the vagus nerve’s healing power on command more easily. Some people may be able to reengage their own dysfunctional vagus nerve through mindfulness exercises, but most need an external aid. That includes many who live with long COVID, given that they often have severe tissue damage and depleted energy levels. “To tell somebody who has struggled with long COVID for three years and has seen 500 doctors to go do some mindfulness—that’s not going to go over well,” says Mayo Clinic internist Ravindra Ganesh, who is currently leading a clinical trial of vagus nerve stimulation for long COVID using electroCore devices.

During the early days of the pandemic, researchers quickly noticed that several symptoms of acute COVID infection were similar to those of the vagus nerve going haywire. People hospitalized with COVID often suffered from the so-called cytokine storm, in which the infection triggered an excessive, runaway immune response that eventually turned inward to wreck the host’s own tissues.

After the initial infection waned, a large percentage those experiencing long COVID still reported symptoms typically seen with vagal dysfunction. And this past June researchers found smoking-gun evidence: postmortems of deceased people who had COVID revealed viral RNA and inflammation cells in the vagal tissues, indicating the virus had infiltrated and damaged this key nerve.

To many researchers, jump-starting a decommissioned vagus nerve seemed like an obvious solution for treating long COVID. “It's a really fundamental nerve,” says Michael VanElzakker, a neuroscientist at Massachusetts General Hospital. Targeting it as a treatment approach “really ought to be considered and deserves more research.”

The Long COVID Connection

Researchers think vagus nerve stimulation weakens long COVID symptoms by turning up the body’s parasympathetic pathways. One sign of heightened sympathetic activity is when an immune system keeps firing up, even after the initial infection has passed. The vagus nerve quiets this overactive defense by reducing the production of cytokines, signaling chemicals that promote inflammation. In 2000 researchers discovered the vagus nerve’s anti-inflammatory role when they found that stimulating it reduced lethal septic shock in rats exposed to bacterial toxins. Many scientists think reactivating the vagus nerve could also potentially reset immunity in people with acute COVID or chronic symptoms.

Rousing the portion of the vagus nerve entering the brain stem might also engage neighboring cortical areas that are involved in memory and attention, according to Elisabetta Burchi, head of translational research at the neuromodulation start-up Parasym. Such stimulation sets off a release of neurotransmitter chemicals, which may help reduce long COVID’s neurocognitive effects. The evidence is still inconclusive, though. One preprint study that’s awaiting peer review found that vagal stimulation had only a minimal impact on “brain fog,” a frequently reported symptom of long COVID.

So far pilot studies have demonstrated that vagus nerve stimulation works best for reducing long COVID’s debilitating fatigue. Researchers have been encouraged that some participants in these studies reported improvements—but they have noted that some did not. “There is no trial of any drug or anything I’ve ever done in all my years that makes a patient so well that he or she no longer fulfills criteria for chronic fatigue syndrome,” says Benjamin Natelson, a neurologist at Mount Sinai, who has run several clinical studies on vagus nerve stimulation for various health conditions, some of which used devicesfrom electroCore and Parasym. (Natelson says he did not receive funding for the studies from these companies.)

Because the vagus nerve consists of so many fibers, researchers can’t control which individual fiber gets triggered to target any particular organ; multiple parasympathetic pathways get turned on at once during stimulation. This may sound worrying, but researchers agree there aren’t many negative side effects from excessive parasympathetic action. If such a device is used properly, the worst potential complications will probably be mild skin irritation from the electrical zaps or diarrhea from an overstimulated digestive system.

Vagal therapy still has scientific gaps to address, so doctors are hesitant to prescribe it broadly for long COVID before a confirmatory trial is complete. Scientists are still working out treatment details, including the best delivery method. For example, electroCore’s strategy is a series of mild shocks with a handheld device that a user can touch to either side of the neck for a few minutes every day. Staats, the firm’s co-founder, says this is where the vagus bundle is thickest, making it the most effective stimulation site. Other researchers, including those at Parasym, say taming long COVID’s symptoms requires a longer stimulation time. These scientists note that the tip of a vagal branch ends in the folds of the ear. Wearing a hands-free, earbudlike clip there could be a relatively convenient way to deliver an hour of electrical stimulation daily.

But electrically stimulating the neck or ear might not activate the entire vagal column, argues Gemma Lladós, an infectious disease physician at the Germans Trias i Pujol University Hospital in Spain. She suggests a more invasive approach: a device implanted under the skin directly over the vagal bundle to deliver close-up and continuous stimulation, similar to implants for epilepsy and depression. Lladós’s team is finalizing plans for a 2024 clinical study on treating long COVID with a vagus nerve implant.

Sticker Shock

There’s also one glaring caveat to vagus nerve stimulation: the price. The electroCore device, for example, is offered on a pay-per-use basis that can cost a person more than $7,000 per year without any discounts. Parasym’s stimulator has a one-time price tag of €699 (approximately $770) and is only sold in Europe (though Natelson says some of the people he treats in the U.S have managed to purchase the device by using European addresses). U.S. regulators have approved electroCore’s device and some other companies’ versions as well—but exclusively for non-COVID-related problems such as migraines. People with long COVID can buy these products only if their physicians prescribe them off-label, and insurance companies are unlikely to cover the cost without specific approval for long COVID.

Researchers caution against trying to build one’s own device or purchasing untested versions on the Internet. Vagus nerve stimulation involves running an electrical current close to your heart or brain. “Let’s not mess with that,” Ganesh says. Approved medical devices are calibrated to be safe, but an unapproved device with incorrect settings could slow or stop the heart. In extreme cases, vagal tampering can lead to sudden death.

As with any long COVID therapy, the key is pacing to ration one’s energy levels according to the body’s limits, Grach says. At the Mayo Clinic, she often sees patients who are so excited to embark on a new treatment that they push their body too far and eventually crash. “If you continue to push past the reserve that your body has,” Grach says, “you're not going to end up feeling the benefit of the interventions regardless.”