John Feal, now 54 years old, was a supervisor at a demolition company when terrorists hijacked two planes that brought down the World Trade Center buildings—and two others that crashed into the Pentagon and a field near Shanksville, Pa., respectively—20 years ago. Feal, who hails from Long Island, N.Y., arrived the day after New York City’s iconic buildings came down. He had been working at Ground Zero for five straight days when 8,000 pounds of steel crushed his left foot.

Feal spent 11 weeks in the hospital, eventually developing gangrene, losing half of his foot and relearning how to walk. He has since undergone 42 surgeries and developed arthritis in about 80 percent of his body, and he suffers chronic problems with his hips, knees and lower back. Feal created a foundation that has been instrumental in fighting to ensure 9/11 responders and survivors receive the health care they deserve for the sacrifices they made.

“Most Americans just think two buildings came down that day and innocent lives were lost to senseless violence, and that did happen,” Feal says. “But many don’t know that tens of thousands of people got sick, and many have died since then from their illnesses contracted at Ground Zero.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Nearly 3,000 people died during the deadliest terrorist attack in world history. But in the two decades since then, the number of deaths among survivors and responders—who spent months inhaling the noxious dust, chemicals, fumes and fibers from the debris—has continued creeping up. Researchers have identified more than 60 typesof cancer and about two dozen other conditions that are linked to Ground Zero exposures. As of today, at least 4,627 responders and survivors enrolled in the World Trade Center (WTC) Health Program have died.

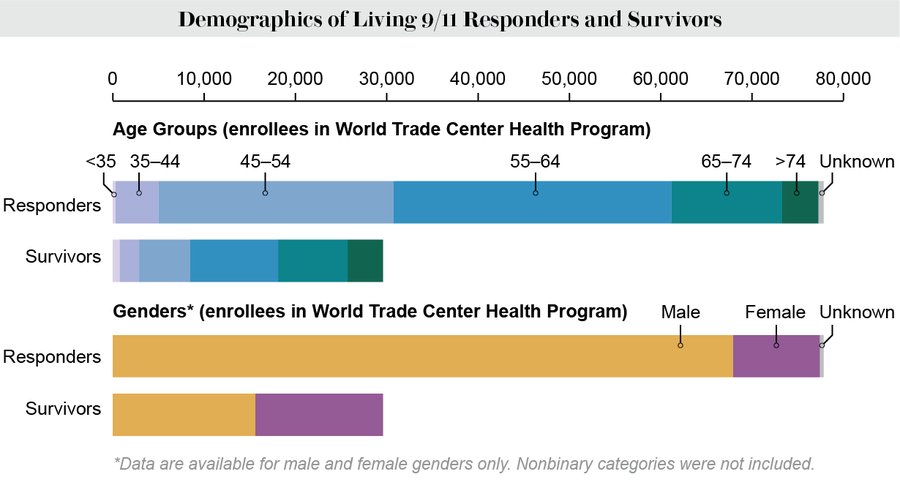

Not all those deaths can be attributed to conditions linked to Ground Zero exposures: the WTC Health Program tallies members who have died for any reason, including accidents and conditions unrelated to 9/11, in the 20 years since the attacks. But the program—established to provide health care for 9/11-related ailments in responders and survivors—has had only a bit more than 112,000 members, a fraction of the estimated 410,000 first responders, cleanup crew workers and survivors exposed to all that contaminated air. There are undoubtedly others who have died from 9/11-related conditions who were not enrolled in the program.

Credit: Amanda Montañez; Source: Program Statistics, World Trade Center Health Program, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

“With the 20th anniversary of 9/11 approaching, it is impossible not to reflect on how the World Trade Center attacks continue to exert a painful human toll,” says Moshe Shapiro, a researcher at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, who has published research on the disaster’s health effects. “I have spoken to many World Trade Center responders and am struck by one enduring theme: despite the medical and other consequences of the exposure, they say they would respond again in a heartbeat.”

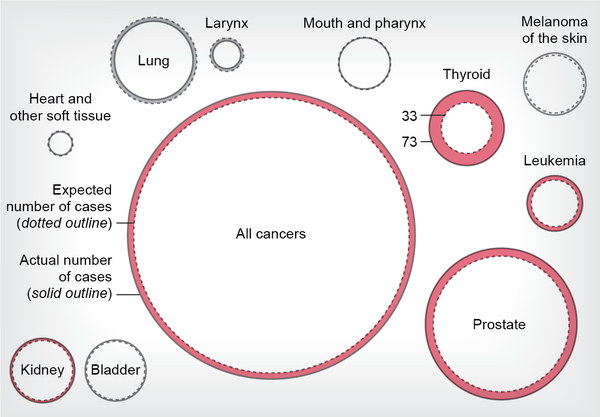

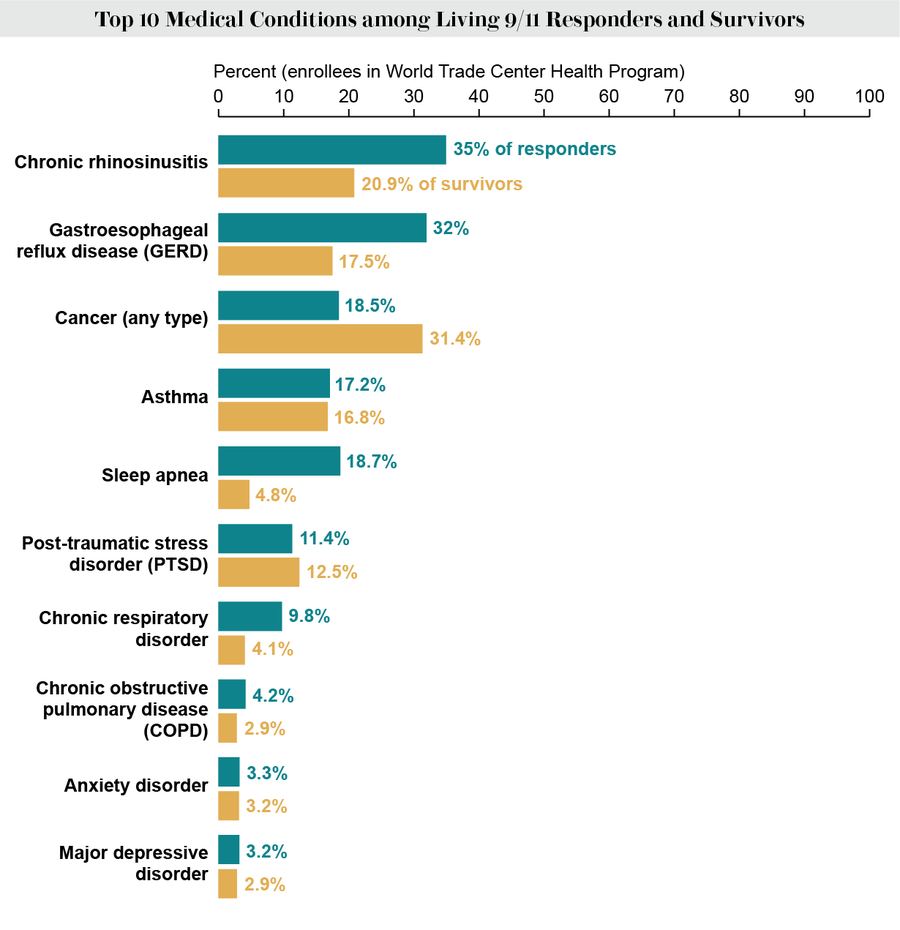

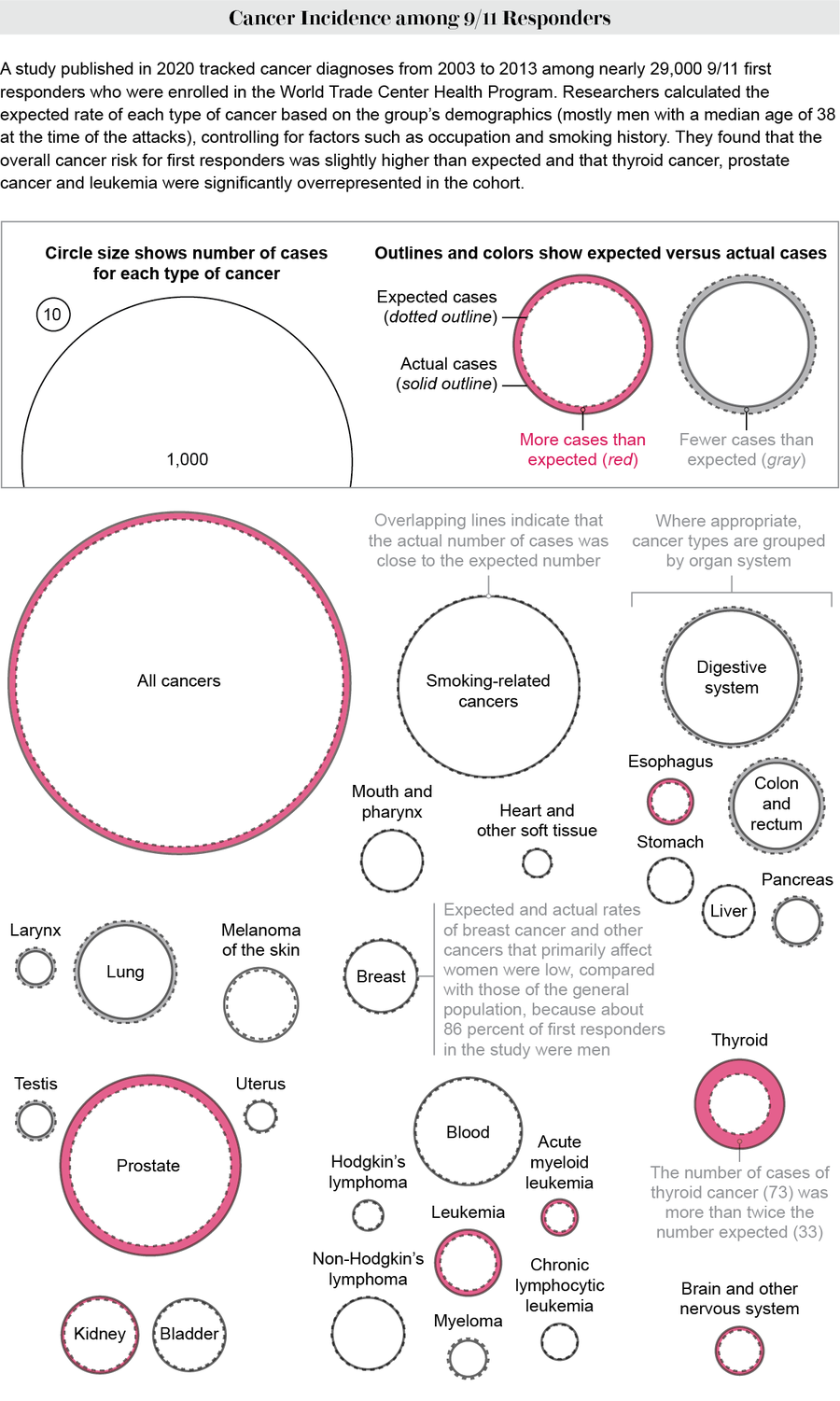

Many of these hundreds of thousands of Americans live with the memory of 9/11 every single day, not just once a year when the anniversary rolls around. The health effects from environmental exposures in the days and months after the attack linger—or develop anew as cancers begin to form. About 74percent of responders in the WTC Health Program have been diagnosed with at least one physical or mental health condition directly linked to 9/11 exposure, including 20 percent with cancer and 28 percent with a mental health condition. The two most common conditions among enrolled responders are chronic rhinosinusitis, or nasal inflammation, and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), followed by cancer—particularly prostate cancer because 87 percent of living responders are male—asthma, sleep apnea and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Credit: Amanda Montañez; Source: “Cancer in General Responders Participating in World Trade Center Health Programs, 2003–2013,” by Moshe Z. Shapiro et al., in JNCI Cancer Spectrum, Vol. 4, No. 1; February 2020

“We worked there, we slept there, we went to bed there, we ate there, we cried there,” Feal says. “The absorption through the nose, mouth and skin of those toxins made us sick.” During the first decade after the attack, he says, he and other responders, researchers and supporters had to fight to prove those health effects were real.

“We said we were sick from 9/11,” Feal says. “They [members of Congress] said we were making it up, it was in our heads, we were crazy. But we’re a finite number, and with these life-altering illnesses, we were dying off quicker than we were supposed to.”

The long-term health impacts were no surprise to epidemiologists such as Christine Ekenga, an assistant professor of environmental health at the Rollins School of Health at Emory University, who studies the health impacts of disasters and has authored several studies on the effects of 9/11.* “Long-term physical and mental health impacts were always a concern among clinicians and health researchers during those early years, and we did anticipate that there would be 9/11-related deaths long after the disaster,” she says.

Today the link between 9/11 and a long list of chronic health problems is indisputable. The WTC Health Program has a list of conditions it will cover that research has definitively linked to 9/11 exposures. And the federal James Zadroga 9/11 Health and Compensation Act, signed into law in 2011 and reauthorized in 2015, ensures that funding will cover care for those conditions through 2090.

Nearly half of living responders have a respiratory or digestive condition related to 9/11, and 16 percent have developed a cancer. Another 16 percent have a mental health condition, such as PTSD, depression or substance abuse. The WTC Health Program covers all of these ailments, as well as musculoskeletal conditions that developed on or after 9/11.

Credit: Amanda Montañez; Source: Program Statistics, World Trade Center Health Program, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Among the hardest hit groups were members of the New York City Fire Department (FDNY), a cohort that includes more than 15,000 firefighters, emergency medical services staff and civilians enrolled in the WTC Health Program. FDNY lost 343 people on 9/11, but more than 200 have died since, according to Rachel Zeig-Owens, director of epidemiology for the WTC Health Program at FDNY. Even two decades after the attacks, 9 percent of FDNY veterans of 9/11 still have PTSD, and 18 percent have depression.

“Most of the fire department was exposed to the heavy dust right at the beginning, and they were invested in trying to help find everybody and do the rescue and recovery work,” says Zeig-Owens, who is also an assistant professor of epidemiology at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. Few of them used respirators or other essential personal protective equipment in the early weeks. The appropriate respirators were not available until a week after cleanup began. Even then, they were bulky and difficult to wear, and they impeded communication. The average time FDNY employees and retirees spent on site was three to four months, although some spent the whole 10 months at Ground Zero until cleanup concluded in July 2002.

One of Zeig-Owens’s key findings that lent evidence to the link between long-term impacts and 9/11 exposures was the dose-response effect. The most common conditions, GERD and upper and lower respiratory disease, each occur among more than 40 percent of FDNY workers, and those who arrived on-site earliest have the highest rates of respiratory disease.

Prostate cancer rates in FDNY members began to increase after slightly more than five years post-9/11—much sooner than the 10- to 20-year increase seen in studies of populations that were not exposed to Ground Zero. Researchers also found that rates of prostate cancer correlated with greater levels of exposure.

Similar evidence is building for conditions that are not yet covered under the WTC Health Program, including heart disease, some autoimmune diseases (especially lupus), hearing problems, and neurological and cognitive conditions. For example, workers who arrived on the morning of 9/11 were 38 percent more likely than those who arrived later in the day or later that week to have a stroke, heart attack or other cardiac event in the years since.

Research on the FDNY cohort also reveals the challenges of disentangling how 9/11 exposures have and have not contributed to different conditions, however. For one thing, FDNY members had better baseline health and tended to have a healthier lifestyle than their peers at the time of the attacks. Only 4 percent of them smoked, a much lower rate than New York City’s general population (although about a third were former smokers). Being healthier to start with may partly explain why FDNY members and other responders enrolled in the WTC Health Program were 34 percent less likely to die of cancer than expected during the past two decades, with particularly reduced mortality rates for colon and prostate cancer. But as members of the WTC Health Program, they also have better access to health screenings and high-quality care. Such benefits mean faster identification and treatment of cancers than the general population.

The increased screening may actually explain the higher rate of at least one of the cancers. For example, FDNY members who were 9/11 responders have a greater risk of thyroid cancer than the general population, yet Zeig-Owens’s research has found that asymptomatic cases accounted for the excess risk, suggesting that rates were higher in this population because of better health screenings. Regular computed tomography (CT) imaging and chest x-rays for cancer picked up more incidental cases before symptoms appeared. FDNY members had higher thyroid cancer rates because they were in a program that looked for cancer more often.

Other questions remain unanswered. GERD, one of the most common long-term effects of Ground Zero exposure, can lead to Barrett’s esophagus, which can develop into esophageal cancer. Currently, Zeig-Owens says, her team is not seeing higher rates of this cancer in the FDNY cohort, but “it may just be a waiting game.” It can take 10, 20, or more years after an exposure for cells to develop into cancer. The average age of FDNY responders on 9/11 was 40, and most responders are now in their 50s and 60s, when cancer risk begins rising as a result of age.

Researchers continue to try to parse out what cancers are developing because of natural aging versus those occurring as a result of 9/11 exposure. A study published in the February 2020 issue of JNCI Cancer Spectrum, for example, compared the incidence of different cancers among 9/11 responders and found a surprising lower rate of lung cancer but an elevated risk of leukemia. “The complex relationship between exposure and cancer development is not fully understood,” says Shapiro, who led the study. But his team has some hypotheses. “Leukemia is associated with exposure to benzene, present in [high] quantity from burning jet fuel at the World Trade Center site,” he says.

Despite the growing list of lingering 9/11 health concerns, the research has uncovered some encouraging findings, such as a lower risk of death from cancer. One recent study identified the factors that play the biggest role in 9/11 responders’ risk of developing lung disease, as well as ways to reduce that risk, such as losing weight and reducing cholesterol.

Now that scientists better understand the effects of this tragedy, “we’re mostly focused on how to help people improve,” says Anna Nolan, a professor of environmental medicine at the NYU School of Medicine, who conducted the lung disease risk study with Zeig-Owens and their colleagues. “Body mass index and lipids are much riskier to these patients than even smoking history, and I think that’s really important” because those risk factors can be changed, she says.

The research on the tragedy’s aftermath can help public health experts and policy makers better understand health effects from other human-made and natural disasters.

The more researchers examine the mechanisms by which particulate matter during the 9/11 cleanup led to inflammation and various health conditions, “the more you realize the similarities to other ambient and urban exposures,” including wildfires, Nolan says.

Feal, for his part, has not wavered in his mission to find those who have slipped through the cracks to help them enroll in the WTC Health Program. And he has continued to honor those who have died by memorializing them in the park on Long Island that the FealGood Foundation helped build.

The COVID-19 pandemic has complicated that aim, and it has taken its own toll on 9/11 survivors. Feal, who says he has “never been afraid of anything in my life ever,” experienced a bout with COVID that terrified him. “I thought I was going to die,” he says. About 100 9/11 survivors have perished from the disease, often alone in the hospital, Feal adds.

But even once the pandemic’s immediate danger passes, 9/11’s impacts will endure. “The further we get away from 9/11, the more these men and women suffer, and we want to comfort them because the next 20 years are going to be a lot worse than the first 20 years,” Feal says. Research supports his prediction.

“Since that terrorist attack 20 years ago, we’ve seen a lot of manmade and natural disasters, and it takes a special breed of people to run toward [them] while others are running away,” Feal says. “These people were truly the best of the best. They were our nation’s greatest resources. They gave hope to a broken city and to a lost country. And we need to do a better job of helping these men and women.”

*Editor’s Note (9/10/21): This sentence has been edited after posting to correct Christine Ekenga’s current title and affiliation.