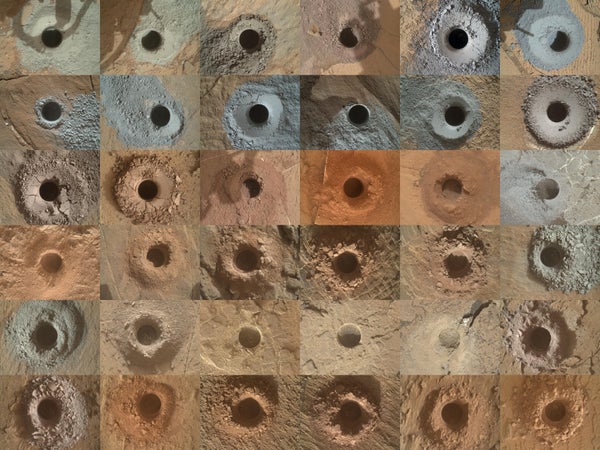

NASA’s proposed Mars Sample Return mission faced another setback in February, when its lead facility, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, laid off nearly a tenth of its workforce. The layoffs—and the lives upended by them—are a direct consequence of a budget battle between the two chambers of Congress, the U.S. House and Senate are arguing over the future of a program that would return a carefully selected set of Martian samples to Earth to answer key questions about the solar system’s history, habitability and evolution.

The MSR mission has been beset by mismanagement, rising costs and now shrinking NASA funding. In response, the Senate proposed to slash its budget by nearly two thirds to $300 million in 2024. The House of Representatives took the opposite track, doubling down on MSR by providing the full $949 million originally requested. No compromise has yet been tendered, though we are well into the fiscal year in question. This stalemate led NASA to throttle spending on MSR to match the lowest of all possible outcomes. Consequently, JPL found itself with a sudden budgetary hole, which forced the rapid layoffs. Other NASA centers such as the Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland have also lost major MSR-related projects, contributing to further workforce stresses and contractor layoffs across the country.

Given the setbacks, some are asking if the project is still worth pursuing. My answer is yes, it is.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

We should do sample return now, while we have the support of our European partners and an experienced NASA workforce with a string of successful Mars landings under its belt. We should do it right by returning the comprehensive set of samples already collected by the Perseverance rover now on Mars. But we must do it with care; absent additional money from Congress, the project must be reimagined, and annual costs kept under control.

MSR is a high-risk project, but the anticipated scientific return could transform our understanding of the solar system and the evolution of rocky planets. The implications of potentially finding evidence of ancient life are even more profound.

Worth noting, the mission offers a compelling connection to NASA’s long-term human exploration effort, which starts with the Artemis lunar landings and then points toward Mars. MSR would validate key technologies for astronaut safety, including precision landing, launch from Mars and automated in-orbit rendezvous in deep space.

To succeed, however, NASA and its partners must address the serious management and design issues raised in a recent independent review. NASA leadership is in the midst of a detailed reevaluation of the project and its implementation, but has yet to make a firm statement about MSR’s future. In the meantime, the Planetary Society, where I work, outlined a set of principles for Mars Sample Return for NASA to consider during this process. Briefly, they state: do the science by returning the full suite of samples, while the expertise and allies exist to pull it off, but don’t wreck NASA’s entire budget in the process.

The ideal solution to MSR’s woes—and the one proposed in formal recommendations to NASA by the scientific community in 2022—is to secure additional funding from Congress. Unfortunately, December’s congressional debt-limit deal froze domestic spending levels; as a consequence, NASA’s science budget appears likely to stay flat, if not outright shrink. It is this monetary pressure, and the growing cost estimate of MSR itself, that led the Senate to propose its cuts.

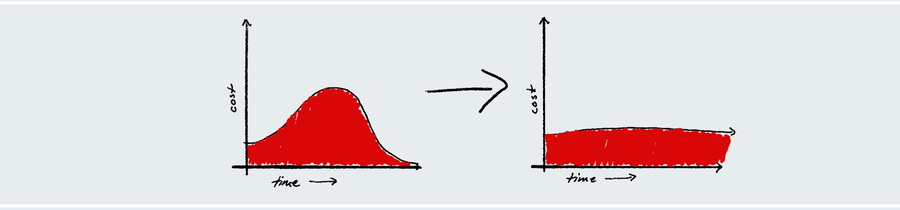

There are two ways to consider “affordability” of space projects: the life-cycle cost and the annual cost. The life-cycle cost is the headline number, the sum of all expenses over the life of the project. The annual number, however, is how much a project spends in any given year. Ideally, aerospace projects follow a curve, where annual spending is low at first, peaks a year or two before launch and then shrinks again as operations commence.

A spacecraft can still get built without an ideal cost curve; just not as quickly.

MSR, as previously conceived, had a headline number between $8 billion and $11 billion. This would place it among the Hubble and James Webb Space Telescopes in total cost, making it one of the most expensive science missions in NASA history. That’s not cheap, though it’s not without precedent. The real trouble was that the annual expenditures necessary for MSR to launch by 2030 would peak above $1 billion per year—an unusually large amount.

Congress allocates funding on a yearly basis. Therefore, annual costs are subject to the most political jockeying. Much of NASA’s program planning is a delicate dance to ensure no one project’s costs peak at the same time as any other. The smaller the annual expenditures, the less disruption to other programs, and the easier a project is to accommodate in the budget.

This perspective provides a potential political solution to MSR. As part of its redesign process, NASA could optimize around MSR’s annual budgetary footprint rather than its programmatic efficiency. Targeting a historical amount, something successfully funded in the past, is one such approach. For example, the average cost of the robotic Mars program last decade was about $600 million per year. It could be a viable amount for near-term progress in MSR.

An “ideal” cost curve for an aerospace project can be flattened out, reducing the annual expenditures at the expense of time and total project cost.

Credit: Casey Dreier/Planetary Society

Notably, controlling annual costs (keeping them less than a third of all planetary spending) was proposed in the scientific community’s official recommendations to NASA about MSR, though I’m suggesting a more significant restriction in light of the severe limits on federal spending passed in 2023.

We should not gloss over the detriments to this approach. There are operational, managerial and design compromises required to maintain an arbitrary cost limit in service of political expediency. “Quality, cost, time—pick two” is an adage of the aerospace industry. If quality is fixed (MSR must work, as there are no backup samples), and annual costs restricted, then time must give. This will delay the return of samples, possibly by many years. And, perhaps ironically, it means that the headline cost itself will be much larger, since a large workforce will be on the books for much longer than otherwise.

The alternatives are even less realistic. SpaceX is building a massive Starship and its first-stage Super Heavy rocket, with the explicit goal of establishing a Martian settlement. Why not wait for Starship to bring back tons of rocks instead? Because swapping MSR for Starship trades a hard problem for an extremely hard one—sustaining human life on a round-trip mission to Mars. Additionally, there is no guarantee that Starship will succeed at Mars, or that it would return scientifically relevant samples.

JPL’s job losses are the most visible symptom of a growing budget calamity at NASA centers around the country. It is, sadly, politically self-inflicted. That doesn’t mean now is the time to shirk away from our ambition and abandon our most fundamental and important questions. The opportunity to unlock a vast history—the history of the solar system and perhaps even the history of past or present life—is too great to abandon. The path forward will be messy, probably suboptimal, and require ongoing debate—but that’s democracy for you. It just means now is the time to argue for the big picture and for our better angels: loosing our wild ambitions on the hardest tasks for the most peaceful of reasons.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.