Imagine a weapon with no human deciding when to launch or pull its trigger. Imagine a weapon programmed by humans to recognize human targets, but then left to scan its internal data bank to decide whether a set of physical characteristics meant a person was friend or foe. When humans make mistakes, and fire weapons at the wrong targets, the outcry can be deafening, and the punishment can be severe. But how would we react, and who would we hold responsible if a computer programmed to control weapons made that fateful decision to fire, and it was wrong?

This isn’t a movie; these were the kinds of questions delegates considered at the April Conference on Autonomous Weapons Systems in Vienna. In the midst of this classically European city, famous for waltzes, while people were picking up kids from school and having coffee, expert speakers sat in special high-level panels, microphones in hand, discussing the very real possibility that the development and use of machines programmed to independently judge who lives and who dies might soon be too far gone to come back from.

“This is the ‘Oppenheimer moment’ of our generation,” said Alexander Schallenberg, the Austrian federal minister for European and international affairs, “We cannot let this moment pass without taking action, now is the time to agree on international rules and norms to assure human control.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

I reported on these meetings, these extraordinary discussions about our future happening parallel to the ordinary moments of our present, as the United Nations reporter for a Japanese media organization—Japan being the only nation in history to have experienced nuclear bombings, and thus very interested. And Schallenberg’s statement rang true: the need for international rules to prevent these machines from being given full rein to make life and death decisions in warfare is bleakly urgent. But there is still very little actual rulemaking happening.

The decades following the first “Oppenheimer moment” brought with it a simmering cold war and a world on the edge of a catastrophic nuclear apocalypse. Even today there are serious threats to use nuclear weapons despite their capacity to collapse civilization and bring human extinction. Do we really want to add autonomous weapons into the mix? Do we really want to arm computer screens that could mistake the body heat of a child for that of a soldier? Do we want to live in a world inhabited by machines that could choose to mass bomb a busy town square in minutes? The time to legislate is not next week, next year, next decade. It is now.

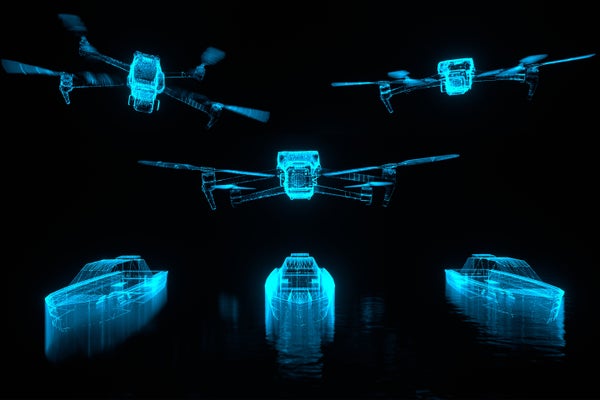

Mention “killer robot,” and your mind thinks The Terminator, but the real killer robots can be much more subtle, posing as computer programs on screens. The weapons themselves can take many forms: unmanned and submersible drones; loitering “suicide” drones that lie in wait for a target before pouncing an attack; defense systems with antivehicle and antipersonnel mines; preprogrammed attack missiles, rockets or aircraft that engage targets based on criteria; or even drone “swarms” used to kill en masse.

Such weapons exist under human control—an actual person deciding when and where to use them—but more and more, programmers are training these machines to make those decisions without a human hitting a figurative red button. How these machines are trained and tested is critically important. Some argue there might still be a chance of stalling the development of even deadlier autonomous weapons, but, even if that is somehow possible, it is clear right now that rules on their use, at least, are needed.

These weapons aren’t even a future problem anymore; there are reports of fully autonomous drones being employed in the war in Ukraine, and an AI-powered database known as Lavender is being used by the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) to track and target members of Hamas. How we use autonomous weapons systems, the ethics behind these decisions, and whether we regulate using them are already hotly debated geopolitical topics; the number of meetings focusing on them, such as the conference in Vienna, has increased exponentially over the past few years.

The main players in the field of world peace have been aware of the threat posed by these types of weapons for some time. Human Rights Watch (HRW) has loudly called for international legislation and has repeatedly stated that use of autonomous weapons would “not be consistent with international humanitarian law.” The HRW also co-founded the aptly named, “Stop Killer Robots” coalition, launched back in 2013, which adamantly campaigns against machines “making decisions over whom to kill”.

In October of last year the U.N. secretary-general, António Guterres, and the president of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), Mirjana Spoljaric, made a joint appeal to states to establish specific prohibitions and restrictions in order to “shield present and future generations from the consequences of their use.” Autonomous weapons systems are also on the agenda of the General Assembly and are expected to be discussed at the Summit of the Future later this year.

Despite these valiant efforts and daunting Oppenheimer statements by officials, progress on legislation remains decidedly lethargic.

What are the reasons? They are multiple, but one thing is for sure: the nations that should be pulling their weight are not.

The U.S. Department of Defense has made statements about autonomous weapons that recognize their dangers but has not adopted clear rules about their development or use, and behind the scenes the DOD is quietly investing in military AI and autonomous weapons technologies. The Pentagon is reportedly already working on at least 800 AI-related military projects as of late 2023, with intentions to field AI-enabled autonomous military vehicles by 2026 in order to keep pace with the technological advances of China. While the U.S. has made public directives recognizing the seriousness of weapons being left to their own programmed judgements, they contain loopholes and previous statements by officials have vague definitions of “appropriate levels of human judgement” among other wishy-washy language. In 2023, the U.S. government proposed a political declaration “to build international consensus around responsible behavior and guide states’ development, deployment, and use of military AI.” But other nations that are developing or showing intertest in AI weaponry, including China, Russia, Iran and India, have not signed on.

Oppenheimer is famous for repeating the quote, “Now I am become Death, Destroyer of Worlds” upon creating the atom bomb. Eight decades later, nuclear weapons remain, most of us have not known a world without them and, the way disarmament is going, we are unlikely to ever know one again.

With autonomous weapons, we are on the cusp of another "Destroyer of Worlds" coming into existence. This time it will be a machine. A machine unable to feel. Unable to know humanity. Unable to ever make true human judgement.

The technology is outrunning the legislation, and it is beginning to outrun all of humanity too. If more is not done—now, in this moment, by the people who can do it—to control this technology through laws and treaties, then what is to stop a grotesque arms race of killer robots, with lethal autonomous machines and the hanging threat of Terminator-esque war becoming normal? If more isn’t done, couldn’t humanity itself be on the brink?

We have evolved over epochs, built societies, instated human rights, made discoveries, put people into space and cured some of the deadliest diseases. Humans, so intelligent, so revered, so far ahead. Why would we then do something as stupid as allow a machine to judge our life’s worth? Why would we ever risk ending up in a mess of our own inhuman human creation, in the ashes of our own destruction, because we gave algorithms and codes the ability to terminate human life? The trajectory continues, unless we change it.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.