Earlier this month a person in rural Oregon was diagnosed with plague—the state’s first case in eight years. According to health officials in Oregon’s Deschutes County, the person likely contracted the disease from a pet cat.

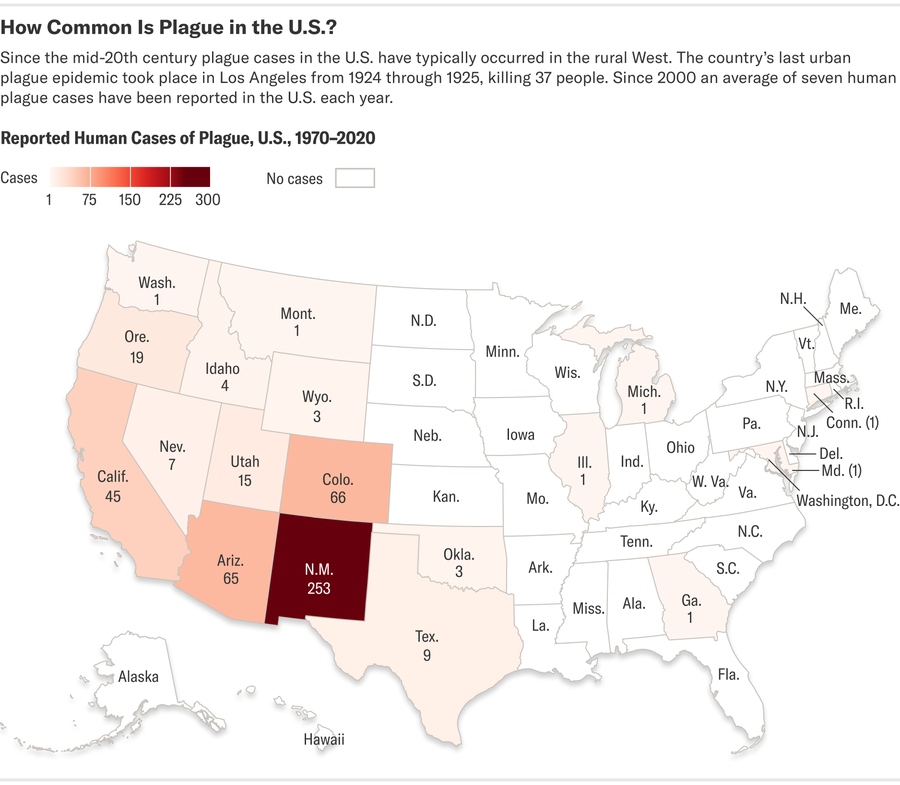

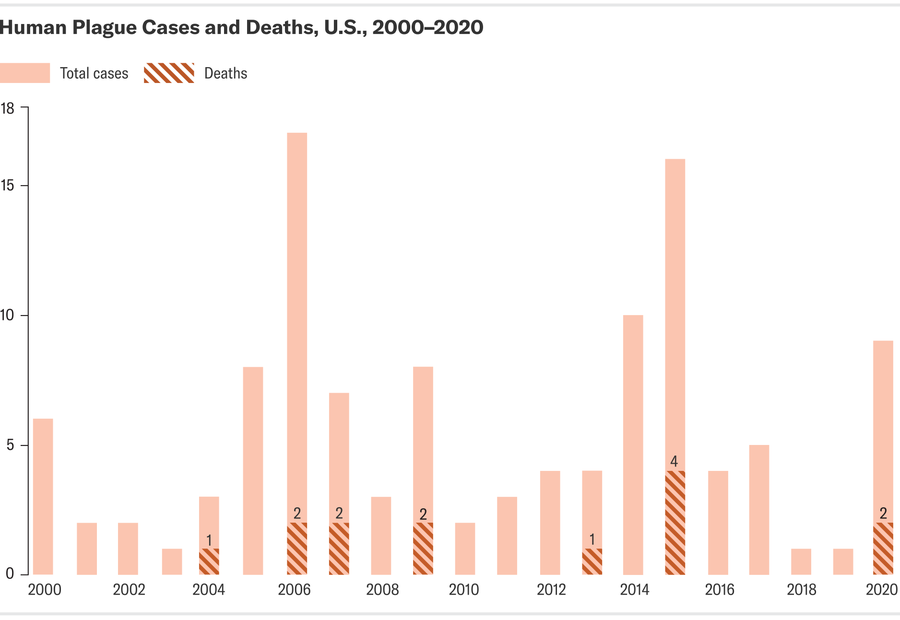

Plague is often thought of as a medieval disease, but it continues to affect people across the globe—most commonly in Madagascar, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Peru. In the U.S. about 10 cases of plague are diagnosed per year. Most of these are reported on the West Coast and in Southwestern and Rocky Mountain states—particularly in New Mexico.

Credit: Shuyao Xiao; Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (data)

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Plague is caused by a bacterium called Yersinia pestis. Most people know it as the microbe behind the “Black Death,” which wiped out at least a third of Europe’s population in the 14th century. Humans and the animals that travel with them have spread it to every continent except Antarctica. It most likely arrived in the U.S. on ships docking in California sometime around the year 1900.

Y. pestis can make humans extremely ill, but it doesn’t naturally thrive in human populations. Instead it lives in wild rodents. “It doesn’t make them particularly sick, and so that means it can just kind of quietly circulate in that population,” says Erin Phipps, state public health veterinarian of New Mexico. The particular rodent species that carry plague can vary from region to region, but in the U.S. it can be found in rats, prairie dogs, marmots, squirrels and, occasionally, chipmunks.

From these “reservoir” species, plague can spread to other animals via fleas. If a flea bites an infected rodent and then leaps onto another animal, its bite may transmit some of the Y. pestis bacteria. This can happen in humans, but it can also happen to animals closely associated with us. “Cats are very susceptible to Yersinia infection” because they tend to hunt rodents specifically, says Susan Jones, a biomedical historian at the University of Minnesota who is working on a book tracing the history of plague in the former Soviet Union.

Even today the disease can be deadly for both humans and pets who contract it if left untreated. Unlike medieval physicians, however, modern doctors are well equipped to deal with the illness, thanks to antibiotics.

“Antibiotics work very well against plague,” says Javier Pizarro-Cerdá, a systems biologist at the Pasteur Institute, a nonprofit research organization in France. “But we have to diagnose [it] early for them to be effective.”

Credit: Shuyao Xiao; Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (data)

By far the most common form of plague is bubonic plague. It’s characterized by painful swollen lymph nodes called “bubos” around the armpits, throat and groin. Bubonic plague is the easiest type of plague to diagnose and the most survivable. It is primarily spread by flea bites.

Sometimes Y. pestis travels from the lymph nodes into the lungs to become “pneumonic” plague. “Once the bacteria arrive in the lungs, they are very, very happy there. They proliferate like crazy,” Pizarro-Cerdá says. This form of plague is transmitted directly through respiratory droplets, much like SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID. It also triggers a fairly generic—though severe—set of symptoms, including fever, body aches, cough and shortness of breath. Pneumonic plague is more deadly and more difficult to diagnose than bubonic plague.

Very rarely, a person might contract a third form of the disease known as septicemic plague. This occurs when Y. pestis bacteria enter and begin to multiply in the bloodstream. People can be exposed to this form of plague through flea bites but also from handling the corpses of infected animals. Left untreated, septicemic plague is nearly always fatal. There is not currently a vaccine against plague commercially available in the U.S. The plague vaccines that have been approved under certain circumstances in other countries aren’t very effective, but groups such as Pizarro-Cerdá’s are working to develop a better shot.

Luckily, for most people in the U.S., avoiding plague isn’t difficult. The first step is to be aware of your surroundings when hiking or exploring wilderness areas in the western part of the country. If you are in an area where plague is endemic, make sure to wear long sleeves and pants, carry insect repellant and avoid dead animals, Phipps says. In addition, people who live in states where plague is endemic should take measures to avoid attracting rats or other rodents to their home, such as keeping outdoor animal feed in sealed containers and not letting wood or garbage pile up in the yard. Keeping cats indoors can also decrease the likelihood that they will become infected by a plague-infected rodent.

If you think you may have been exposed to a plague-carrying animal, you should let a doctor or health official know right away so that they can treat you. At the end of the day, “humans cannot completely separate ourselves from the natural environment,” Jones says. Some risk of disease is unavoidable—but it doesn’t have to be deadly.