The world has now learned of a surprising scientific advance: so-called “synthetic embryos.” Their arrival promises to reveal to medicine previously hidden glimpses into problems of early pregnancy. And despite echoing old moral concerns about embryonic research, these new lab-made creations differ in essential, telling ways from real human embryos.

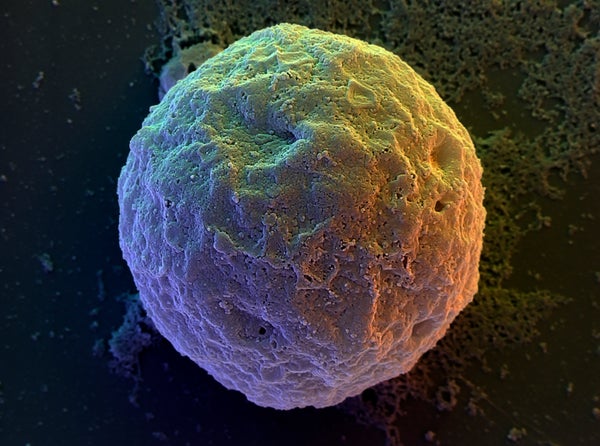

Unveiled at an international stem cell conference in June, “synthetic” may be too strong a word for these biological models made entirely from real human stem cells. When put together in a dish, and given a few chemical nudges to get them started, stem cells can organize themselves into tiny dynamic structures that resemble, to varying degrees, natural human embryos at the earliest stages of development, remarkably all without the need for sperm or eggs.

That sounds significant enough to revive fears of human cloning, or unethical experiments on embryos. But it’s time to take a deep breath and take stock of the realities. An up-to-date understanding of policy and biology will help us shrug off these anxiety-provoking scenarios.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

While “artificial” in the sense that they are of bioengineered origin, stem-cell-generated embryo models could reveal important real-world truths about both assisted and unassisted reproduction, pregnancy failures and the causes of many developmental disorders. They offer a new model system for researchers to probe the mysteries of human development corresponding to when embryos become embedded in the uterus. This brief period of time, from six to 28 days post fertilization, is referred to as the “black box” of human development. Scientists and physicians know precious little of what happens during this crucial time after the embryo implants in the womb and goes from a clump of cells to its initial elongated shape. This is when many pregnancies fail and many developmental disorders are thought to arise. Unlocking this black box could lead to better infertility treatments and understanding of how certain birth defects originate.

In offering a key to unlock the black box of human development for doctors and patients, could human embryo models pry open a Pandora’s box for humanity? Politicians and research funding agencies might worry that embryo models in the lab could turn out to be so close to the real thing that doing experiments on them would be morally equivalent to doing experiments on natural human embryos, which a sizable portion of the public opposes. Others might fear that human embryo models might be used for reproductive purposes that would take us too far away morally from current practices. Without the need for sperm and eggs (and thus biological parents), children brought into existence through embryo modeling would be later-born clones of whoever was the genetic source of the original stem cell line. Are these controversies inevitable as the science of embryo modeling moves forward?

No. First, let us look at policy. Building off the recommendations of bioethicists and scientific leaders, the International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) issued professional guidelines in 2021 that prohibit the transfer of human embryo models into a human or nonhuman uterus (i.e., no embryo modeling activities aimed at reproductive use). To comply with these guidelines, experiments must first be reviewed and approved by ethics oversight committees before teams can commence any work. And attempts to generate pregnancies using human embryo models are a no-go zone under the rules.

Similarly, and perhaps more important given its regulatory authority, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), along with its counterparts abroad, will not allow the transfer of embryo models into a woman for any reason, because these lab constructs would be classified as highly manipulated biologic products requiring all the steps needed for FDA approval, safety and oversight.

But what if someone wants to break the rules? What is to prevent someone from trying to turn embryo models into babies in jurisdictions with weak enforcement? Or what if the FDA eventually does allow some bold research teams to try to use embryo models for reproduction, once all the legal hurdles have been cleared?

Here is where biology comes in to provide a reality check. As alluded to above, stem-cell-generated-embryo models can mimic natural human embryos across a range of early developmental time points. However, not one can biologically produce a baby.

Embryo models that mimic postimplantation stages are simply too far along in their developmental sequence to successfully transfer into a uterus to establish a pregnancy. There would simply be no extraembryonic tissues at that time to welcome and nourish a postimplantation stage embryo model. In the course of normal reproduction, an embryo at that stage would have already burrowed deep within the uterine lining, surrounded by support tissues that it had been building all around its maternal environment.

What about preimplantation models of human embryos that mimic the blastocyst stage of natural embryos—that is, the stage at which doctors transfer fertility-clinic embryos into a patient’s uterus? The answer lies in a fact unknown to people outside the small circle of stem cell experts who generate blastocyst models. To build these preimplantation embryo models, scientists have to begin with specially modified “naive state” human stem cells that have had all their parental imprints removed from their DNA. Stem cells that do not undergo this genomic imprint scrubbing will simply not generate preimplantation embryo models. Here is the kicker: parental DNA imprints are necessary for embryos to be able to develop into a viable fetus. So, the methods that generate preimplantation embryo models simultaneously strip them of their full developmental potential.

In short, embryo models are not equivalent to real human embryos. They lack their exact shape, as well as many specialist cells.

Nonetheless, another critical function they might provide someday is to serve as a platform for drug safety screening to support healthier pregnancies. Almost all medicines that women are prescribed when they are pregnant have zero data on their effects on the developing embryo. Embryo models at various stages of development could be produced in statistically significant numbers under controlled genetic and chemical conditions and screened against each of these drugs. Because embryo models could be used as instrumental tools such this in the future, it is crucial that they not be engineered to be any closer to the real thing than is necessary. With so much socially valuable knowledge human embryo models might produce, it is crucial that we not allow unfounded fears to dampen this important new field. After all, “Nothing in life is to be feared, only understood,” observed Marie Curie in a widely attributed quote. “Now is the time to understand more, so that we may fear less.”

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.