Millions of people are about to gain access to a lifesaving medicine for drug-resistant tuberculosis (TB). A few weeks ago, after years of both quiet and noisy pressure, pharmaceutical giant Johnson & Johnson (J&J) opened the door to inexpensive generic versions of its patented TB drug bedaquiline in several low- and middle-income countries. The new generic medications could cost just $8 per month.

The arrangement was announced in mid-July right after John Green, a young adult novelist and YouTube star—whose channel, which he hosts with his brother Hank Green, has 3.7 million subscribers—spurred an online campaign to hold J&J accountable for “evergreening” its patent, a way to maintain high prices. Within days, the J&J generic deal was made public. But while many have speculated the online campaign played a decisive role, people deeply involved in the negotiations say it was mainly a result of months of quiet pressure rather than high-profile social media moves.

J&J’s global patent of bedaquiline ended on July 18, but the company continued to control access to the drug in many low-income countries where the vast majority of TB cases occur. The company exerted this control via secondary patents: minor tweaks to the drug’s formulation that companies patent and use to prolong—or evergreen—a monopoly. With such patents enforced, bedaquiline costs at least $45 per month. But the July agreement gave the nonprofit Stop TB Partnership licenses that will enable its Global Drug Facility (GDF) to procure and supply the inexpensive generic versions to 44 countries.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The deal is the first of its kind. “You can’t oversell how important and historic this is,” says Lucica Ditiu, executive director of the Stop TB Partnership. While companies sometimes negotiate licenses with a few individual general suppliers, it’s unprecedented for a major pharmaceutical corporation to partner with a nonprofit global supplier such as GDF. In late July, GDF called generic manufacturers to bid on supplying bedaquiline.

J&J and GDF’s deal follows a years-long movement to expand access to one of the most effective medications for TB, the world’s deadliest infectious disease, which afflicted 10.6 million people and killed 1.6 million in 2021. “If you know anything about large pharmaceutical companies like Johnson & Johnson, you know that you can’t bring them to the table and make this kind of deal happen in just a week,” says Brenda Waning, the chief executive of GDF. She says that GDF and J&J reached a verbal agreement in January, J&J provided the license in June, and the actual processes to use the license were finalized on July 15.

Still, some TB advocates argue the new GDF arrangement is only a limited victory. J&J will still control drug access and be able to charge higher prices in countries excluded from the deal, such as Ukraine and South Africa, they point out. Nevertheless, experts say this deal and public campaign could serve as an important model for future partnerships between pharmaceutical companies and public health advocates.

A Crucial Drug

Before bedaquiline was introduced in 2012, most TB treatments had toxic side effects and couldn’t treat drug-resistant strains of the disease. Phumeza Tisile, a 33-year-old TB advocate in Cape Town, South Africa, who was diagnosed with a multidrug-resistant form of the illness in 2010, endured months of laborious treatment regimens. Tisile eventually lost her hearing as a result of painful daily injections of kanamycin, an older TB medication. “It was either I die or go deaf. I didn’t have a choice,” she says.

As the first new TB medicine in more than four decades, bedaquiline quickly became a linchpin of TB treatment because of its superior effectiveness and safety. But the drug was also expensive: a six-month course of bedaquiline originally cost $900 in low-income countries, although J&J eventually lowered that price to $340 in 2020.

Even that cost was prohibitive for public health agencies in many low-income countries, which often opt to buy fewer courses of bedaquiline and use older, more toxic TB drugs because they are cheaper. “We have the drugs to cure patients of tuberculosis, but treatment is out of reach for so many people because of the sheer cost,” Tisile says. “The idea that people are forced to make the same choice I did—die or go deaf or experience some other horrible side effect—when they don’t need to anymore, it makes me so sad and frustrated. It should be patients over profits.”

Although the primary patent on bedaquiline expired on July 18, J&J holds several secondary patents in 44 countries that GDF supplies. Most of these protections extend to 2027. This would have prevented bedaquiline from reaching some of the people in these countries, wherethree quarters of TB cases occur each year. J&J has defended its secondary patents by arguing that the profits it makes are vital for developing innovative medicines to eradicate diseases such as TB. In contrast, “Generic manufacturers ... do not typically reinvest in the development of new medicines,” J&J said in a statement to the medical news service MedPage Today.

Some TB advocates aren’t convinced by the company’s argument. “I don’t buy it for a second,” says Lynette Keneilwe Mabote, an intellectual property expert who specializes in TB and HIV drugs. Mabote notes that J&J supplied less than half of the funds needed to develop and market bedaquiline, while public sector investments contributed about $455 million to $747 million. “The research and development argument falls apart when you realize bedaquiline is actually a global public good,” she adds.

Growing Pressure

The campaign to secure global access to bedaquiline has been mounting for more than a decade. Waning says GDF and J&J have collaborated for several years to procure and distribute TB medicines, including bedaquiline. “During that time, we were very aware of the July 18 expiration date on Johnson & Johnson’s original patent over the drug,” Waning says. GDF feared that J&J’s secondary patents could lead to patchwork availability of bedaquiline: the company could uphold its monopoly in some countries, while others gained access to potentially less regulated versions of the drug. “Last year, we realized it was now or never, and we had the chance to make a big proposal.”

Over several months, Stop TB Partnership met with J&J to negotiate a deal for global generic licenses. Waning explains that one of J&J’s primary concerns was unfettered development and use of bedaquiline, which could contribute to long-term antibiotic resistance. “You want to make sure that your market is such that you have supply security and that quality products are provided in a responsible manner,” Waning says. “I think that’s something that was very attractive about GDF to J&J. We can act as stewards for bedaquiline.”

While these discussions were happening behind-the-scenes, global TB advocates waged a public battle. For example, Tisile and fellow TB survivor Nandita Venkatesan filed a legal challenge against J&J in 2019 to prevent the company from enforcing its secondary patent over bedaquiline in India. This March the duo learned that their petition was successful. “That was one of my proudest moments,” Tisile says. “It was proof that we could fight for greater access and win.”

J&J provided the necessary licenses for GDF to procure generic bedaquiline on June 13, which Ditiu calls “another major milestone.” She believes Stop TB Partnership’s campaign was successful because of the united, well-coordinated push across global health agencies, intellectual property specialists, and private partnerships. “It’s not easy to create this love affair across these sectors because there are many different interests,” she says. “It’s like walking on a minefield, trying not to activate any explosives.”

Ditiu also says it was crucial to spotlight TB patients and survivors in advocacy efforts to combat ongoing stigma surrounding the disease. “We place patients at the forefront,” she says. “There’s no secret ingredient to success—just a lot of hard work and advocacy from many people, including some within Johnson & Johnson.”

The public part of the pressure campaign intensified as the bedaquiline patent expiration date approached. On July 11 Green, who has 4.5 million followers on Twitter in addition to his millions of YouTube subscribers, released a video entitled Barely Contained Rage: An Open Letter to Johnson & Johnson. He pleaded with his followers to put pressure on the company, citing J&J’s own mission statement: “We believe our first responsibility is to the patients, doctors and nurses, to mothers and fathers and all others who use our products and services.”

“We were seven days away from Johnson & Johnson’s patent expiring, and I made the video because I couldn’t imagine a crueler use for secondary patents,” says Green, author of books such as The Fault in Our Stars and Paper Towns. “By unleashing my fanbase, I knew it was going to bring a lot of pressure on the company. But I didn’t know how much.”

The J&J-GDF was publicly announced two days after Green’s video was released, about a week earlier than originally planned. “The campaign popularized the issue,” Ditiu says. “The deal would have happened, but it wouldn’t have been announced on such a big scale.”

More Access and Better Testing

While the partnership has been deemed a victory, advocates say it still falls short in certain aspects. The deal excludes several high-burden TB countries who do not procure their drugs through GDF, including Indonesia and South Africa. “I cheered when I saw the announcement and imagined a future of bedaquiline for all,” says Tisile, who currently lives in South Africa. “But then I read the fine print.”

Mabote, who is also based in South Africa, wants to capitalize on the current momentum and persuade J&J not to enforce its secondary patents in the excluded countries. Alternatively, she says, governments can override these patents and purchase bedaquiline from generic manufacturers to make the medication more accessible. “The fight hasn’t stopped for me or for anyone else living in one of these countries,” Mabote adds.

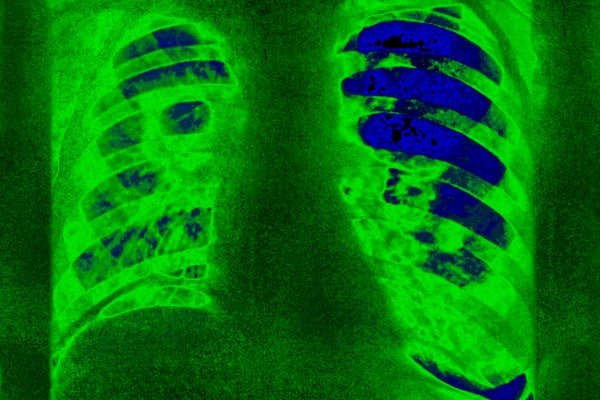

Some experts say the next frontier for TB advocacy will be more effectively diagnosing the disease. Nearly four million TB cases go undetected every year. Many people with TB are also initially misdiagnosed, in part because some low-income countries lack gold-standard screening tools, such as chest x-rays, and instead rely on less accurate but more affordable methods, such as physical exams. Tisile, for example, was misdiagnosed twice, which caused her to receive the incorrect medication for months.

The two issues of underdiagnosis and restricted access to low-cost TB drugs are inseparable, says Helen Cox, an epidemiologist at the University of Cape Town in South Africa, who specializes in TB. “Patents on drugs like bedaquiline make TB so expensive to treat,” she says, adding that many high-burden TB countries are reluctant to fund diagnostic services. “If you don’t diagnose the problem, you don’t have to pay for the treatment.” She’s hopeful that the recent J&J-GDF agreement will encourage these countries to invest into diagnosing TB.

Green also believes that improved access to diagnostic tools is the next step. “The only thing in Johnson & Johnson’s statement that I 100 percent agree with is the last paragraph, where they acknowledge that one of the primary barriers to treatment is the fact that many people don’t get diagnosed with any imaging or molecular tests,” he says.

Currently, U.S.-based corporations such as Cepheid hold a monopoly over TB DNA diagnostic tests such as GeneXpert MTB/RIF and MTB/RIF Ultra, which are priced at $9.98 per test cartridge. The Doctors without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières Access Campaign, which advocates for affordable medical treatments, has argued that public funds largely underwrote the development of these tests. Organizers have also claimed that Cepheid’s manufacturing costs are estimated to be as low as $3 per cartridge, meaning the company could still make a substantial profit if it lowered the costs of cartridges to $5.

“Lowering the price of diagnostic tests is the next fight, and I’m confident that Johnson & Johnson will join us in that battle based on their statement,” Green says. “And if Cepheid pushes back, well, it’s sunny in California,” which is where Cepheid’s headquarters are located. “Maybe we’ll take a trip there.”