Semen was once assumed to be naturally microbe-free; any bacteria found in the fluid was assumed to be a sign of infection. But research over the past decade has shown that semen has its own microbial community, just like microbiomes of the gut and vagina. And now scientists have completed one of the biggest investigations to date on the semen microbiome’s potential link to infertility. Their new findings, published in Scientific Reports, single out a bacterial species that can also be associated with health and fertility issues in the vaginal microbiome.

The semen microbiome can contain a mélange of microbes. Most come from glands in the upper reproductive tract—including the testes, seminal vesicles and prostate—which contribute various components to semen. “Drifter” bacteria from urine and the urethra can also get swept up in the fluid during ejaculation, and microbes from a person’s blood or from their sexual partners might also take up residence in semen.

But how any of these individual species of bacteria might affect health has largely been a mystery. “I would assume that there are bacteria that are net beneficial, that maybe secrete certain kinds of cytokines or chemicals that improve the fertility milieu for a person—and then there are likely many that have negative effects,” says the new study’s co-author Sriram Eleswarapu, a urologist at the University of California, Los Angeles.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Eleswarapu likens the new research to a “fishing expedition” for bacteria in semen that might be associated with infertility. Around 50 percent of infertility cases are attributed to male individuals and can be identified by doctors, but specific treatment options for sperm are limited and used in select cases. One of the most common procedures is in vitro fertilization, in which a person who can produce sperm only needs to provide a sperm sample, while a person who can become pregnant endures the invasive steps of the process, including hormone drug injections and collecting eggs through an ultrasound probe. Learning how the semen microbiome is involved in infertility—and developing drugs that target specific bacteria—could help even out that burden.

To survey the microbiome, Eleswarapu and his team gathered semen samples from 73 men. About half were fertile and already had children; the other half had originally come to Eleswarapu’s clinic for a fertility consultation. “These are people who have been trying to get pregnant with their partner, and they’ve been unsuccessful,” Eleswarapu says. This latter group’s semen samples had a lower sperm count or motility (the sperm’s ability to swim), both of which can contribute to infertility.

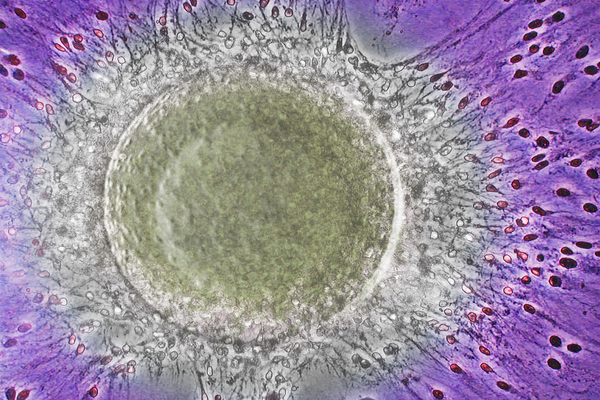

Many bacteria from inside the body don’t grow well in the laboratory, so the researchers turned to genetic sequencing to identify species in the semen microbiome. They found five that were common among all the participants. But high levels of one species, called Lactobacillus iners, corresponded with sperm motility issues in those who were experiencing infertility. L. iners was especially interesting to the researchers because it’s also commonly found in the vaginal microbiome.

Around 90 to 100 percent of a healthy vaginal microbiome is made up of bacteria from the Lactobacillus genus, called lactobacilli, and L. iners is among the four most common species, says Caroline Mitchell, an obstetrician-gynecologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, who wasn’t involved in the new study. To Mitchell, the findings are an indication that the semen and vaginal microbiomes can influence each other.

Still, L. iners isn’t always healthy, or even neutral, in the vaginal microbiome. “Many people have it, and it can be good; it can be bad,” Mitchell says. Some studies show that excessive levels of L. iners in the vaginal microbiome can be associated with bacterial vaginosis, an uncomfortable overgrowth of bacteria. High levels of L. iners in the vaginal microbiome have also been linked to infertility, which lines up with the new findings on the semen microbiome.

Scientists can only speculate about exactly how L. iners could affect sperm motility. It may be related to this species’ production of lactic acid, the same chemical that causes the burning feeling in your muscles during a workout. All lactobacilli produce lactic acid, but L. iners creates a specific variation of the molecule that can induce damaging inflammation—and inflammation has been previously found to impact sperm quality. In the new study, the authors suggest the increased lactic acid from L. iners might prevent sperm from swimming normally.

Other studies have found that several more Lactobacillus species can also harm motility, Mitchell says. Some researchers have hypothesized that the vaginal microbiome’s rich abundance of Lactobacillus slows down unhealthy sperm to increase the chances that a healthy one will fertilize the egg.Having too many lactobacilli in the semen microbiome, however, might hamper even healthy sperm from the start.

Doctors currently treat bacterial vaginosis by combining an antibiotic and a probiotic to help rebalance the vaginal microbiome, and Eleswarapu envisions treating an abnormal semen microbiome in a similar way. The team plans to investigate specific molecules and proteins these bacteria produce and to test whether they slow sperm down in the lab. “If we can identify how they exert that influence,” Eleswarapu says, “then we have some drug targets.”