A first-of-its-kind study in northwestern Saudi Arabia suggests that humans and their livestock have been using a cave for shelter sporadically for up to 10,000 years. The finding offers insight into the region’s history and ecology.

In the past decade, satellite data and fossil finds have suggested that the Arabian Peninsula was not always an arid desert. Periods when the region contained lakes and lush greenery might have drawn people and animals there from Africa, according to the study’s authors.

“Today, it’s a fairly harsh environment,” says study co-author Mathew Stewart, a zooarchaeologist at Griffith University in Brisbane, Australia. Across the surface of Saudi Arabia, “the fossil record is just horrendous”, he says. Wind and scorching heat reduce bones and artefacts to dust, making them difficult to study.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

But in 2018, Stewart and his colleagues described an 88,000-year-old finger bone from the Saudi Arabian desert — one of the oldest human fossils found outside of Africa. And in 2020, they described footprints on a lake shore dating back around 120,000 years. These suggested that the region had stories to give up.

The researchers turned to caves under Harrat Khaybar, a vast basalt plain pocked with volcanic craters in northwestern Saudi Arabia. The caves were made by lava as it flowed from nearby volcanoes, forming rocky tunnels as it cooled.

An excavation near the entrance of one cave produced more than 600 animal and human bones and 44 stone-tool fragments. The oldest stone tools dated back to as many as 10,000 years ago, and the oldest human bone fragments were almost 7,000 years old. The study was published on 17 April in PLoS ONE.

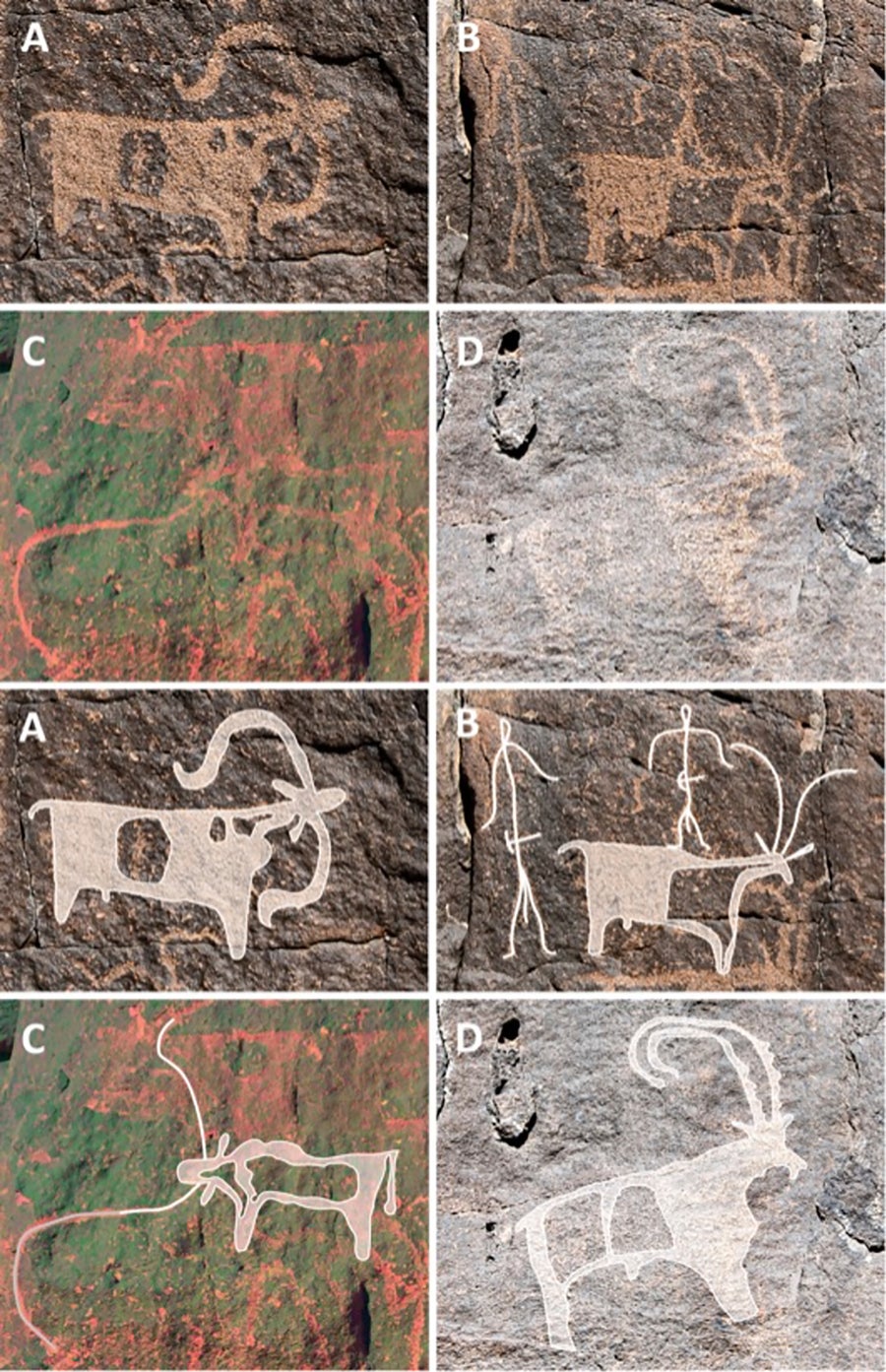

Species identifiable in the rock art of Umm Jirsan. (A) sheep (Panel 8); (B) goat and two stick figures with tools on their belts (Panel 8); (C) long-horned cattle (Panel 6), photo enhanced using the ybk setting on DStretch; (D) ibex with ribbed horns and coat markings (Panel 4). Bottom: tracings of examples A-D.

From “First Evidence for Human Occupation of a Lava Tube in Arabia: The Archaeology of Umm Jirsan Cave and Its Surroundings, Northern Saudi Arabia,” by Matthew Stewart et al., in PLOS ONE, Vol.19, No.4, Article No. e0299292. Published online April 17, 2024

The distribution of samples suggests that people did not live in the cave for long periods, but stayed there occasionally. Nearby rock art depicts people with goats and sheep. The drawings are difficult to date, but they support the fossil evidence that people used the cave as a place to rest and shelter their herds. Even today, farmers seek shade and water in underground lava tubes for themselves and their animals, says Stewart.

According to Melissa Kennedy, an archaeologist at the University of Sydney in Australia, the finding suggests that herders have travelled across Harrat Khaybar from oasis to oasis on the same paths for thousands of years.

Across Harrat Khaybar are paths spanning hundreds of kilometres, some flanked with stone tombs dating back around 4,500 years. Kennedy says the routes were probably used even earlier than the dating of the tombs would suggest. “People are very lazy,” says Kennedy. “You find the easiest route and you stick to it.”

Ahmed Nassr, an archaeologist at the University of Ha’il in Saudi Arabia, says the discovery is significant. “This discovery opens new windows into Arabian research in prehistory,” he says. He hopes that further geographical surveys will be conducted in Saudi Arabia, because they could reveal more such cave sites. “There are many areas that are unexplored.”

This article is reproduced with permission and was first published on April 17 2024.