Researchers say they have uncovered more evidence to support a controversial hypothesis that sticky proteins that are a signature of Alzheimer’s disease can be transmitted from person to person through certain surgical procedures.

The authors and other scientists stress that the research is based on a small number of people and is related to medical practices that are no longer used. The study does not suggest that forms of dementia such as Alzheimer’s disease can be contagious.

Still, “we’d like to take precautions going forward to reduce even those rare cases occurring”, says neurologist John Collinge at University College London who led the research, which was published in Nature Medicine on 29 January.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

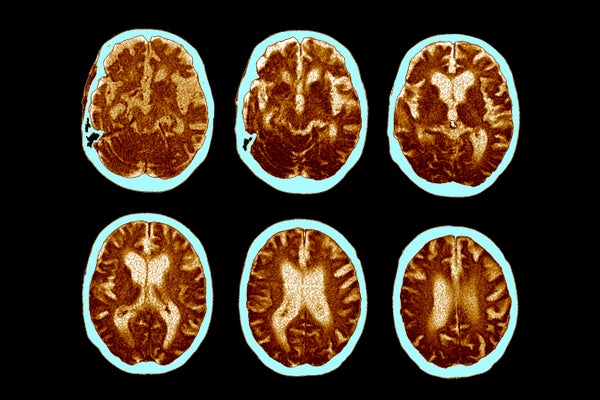

For the past decade, Collinge and his team have studied people in the United Kingdom who, during childhood, received growth hormone derived from the pituitary glands of cadavers to treat medical conditions such as short stature. The latest study finds that, decades later, some of these people developed signs of early-onset dementia. The dementia symptoms, such as memory and language problems, were diagnosed clinically, and in some patients appeared alongside plaques of the sticky protein amyloid-β in the brain, a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease. The authors suggest that this protein, which was present in the hormone preparations, was ‘seeded’ in the brains and caused the damage.

Contaminated hormone

The work builds on the team’s previous studies of people who received cadaver-derived growth hormone, a practice that the United Kingdom stopped in 1985. In 2015, Collinge’s team described the discovery at post-mortem of amyloid-β deposits in the brains of four people who had been treated with the growth hormone. These people had died in middle age of the deadly neurological condition Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, which is caused by infectious, misfolded proteins called prions. The prions were present in batches of the growth hormone.

The four people analysed in that study died before clinical signs related to the amyloid-β build-up might have been observed. But the presence of these amyloid plaques in blood vessels in their brains suggested that they would have developed a condition called cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) — which causes bleeding in the brain and is often a precursor to Alzheimer’s disease.

Collinge’s team also located and studied archived batches of the cadaver-derived growth hormone. In a 2018 study, they reported that certain batches of the hormone preparation contained amyloid-β proteins, and that when such preparations were injected into mice, this led to the development of amyloid plaques and caused CAA in the animals.

This led the team to wonder whether the contaminated hormone preparations might also have resulted in people who received it developing Alzheimer’s disease, in which amyloid plaques are thought to cause the loss of neurons and brain tissue.

In the latest study, the researchers found that five out of eight people who had received the hormone treatment in childhood — but did not develop Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease — developed behavioural signs of early-onset dementia later in life, between the ages of 38 and 55. Collinge’s team argues that these five people — whom the researchers studied in the clinic or through medical records and brain scans — met the diagnostic criteria for early-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

Gene test

Early-onset Alzheimer’s is usually caused by certain genetic variants, but the researchers did not find these variants in three of the people who showed signs of Alzheimer’s and whose DNA samples were available for testing. “This is consistent with these patients having developed a form of Alzheimer’s disease resulting from childhood treatment with this contaminated pituitary hormone,” says Collinge. Taken together, the studies suggest that, in rare cases, Alzheimer’s disease could be transmitted through the transfer of biological material, the authors argue.

However, the study’s small size limits the strength of the findings, says neuroscientist Tara Spires-Jones at the UK Dementia Research Institute at the University of Edinburgh. “Are the amyloid-β seeds from the hormone treatment playing a role in the development of dementia? It’s hard to know with just eight people,” she says.

It cannot be excluded that some of the people might have developed dementia regardless of the hormone treatment, says neuroscientist Mathias Jucker at the German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases in Tübingen. “These people had many different medical conditions which could have increased the risk of developing a neurodegenerative disease like Alzheimer’s disease,” he says.

Researchers including Spires-Jones also question whether the people with dementia actually had Alzheimer’s, despite the clinical diagnoses.

“There are often errors in diagnosing the type of dementia someone has while they’re alive,” agrees neuroscience researcher Andrew Doig at the University of Manchester, UK.

From a public-health perspective, there is no need to be concerned about ‘transmissible’ dementia today, says Spires-Jones. “This treatment doesn’t exist anymore.”

Despite the study’s limitations, the research furthers our understanding of neurodegenerative diseases, scientists say. “I’m glad that people are doing amazing research to help us better understand seeding of neurodegenerative disease by amyloid-β,” says Spires-Jones.

“I think many other scientists will now look for additional evidence to explore the idea of transmissible Alzheimer’s,” says Jucker.

This article is reproduced with permission and was first published on January 29, 2024.