Every spring when the weather turns warm and plants begin to bloom, people start flocking to Neelima Tummala’s ear, nose and throat clinic. They seek remedies for sinus infections, a scratchy throat and other pollen-induced allergy symptoms. And over the past several years, many have complained that their once run-of-the-mill hay fever symptoms are worsening and lasting longer than they used to. One of the likely culprits, Tummala says, is climate change.

As fossil-fuel burning continues to flood the atmosphere with carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, driving up average global temperatures, the planet’s once reliable seasons are also shifting. Summerlike weather often lingers well into fall, and buds are sprouting long before the spring equinox. With toasty temperatures dominating more of the year, pollen and other seasonal allergens can flourish, exacerbating symptoms for the 26 percent of adults and 19 percent of children in the U.S. who experience them. “The prevalence of allergic rhinitis, which is the technical name for nasal seasonal allergies, has increased each year over the past several decades,” says Tummala, who practices in the Division of Otolaryngology at the George Washington School of Medicine and Health Sciences and co-directs the university’s Climate and Health Institute. “Climate change is also impacting the amount of pollen in the air and the length of pollen season.” Scientists haven found a correlation between climate change and worsening pollen allergies, but “it is just not the only contributory factor,” she says.

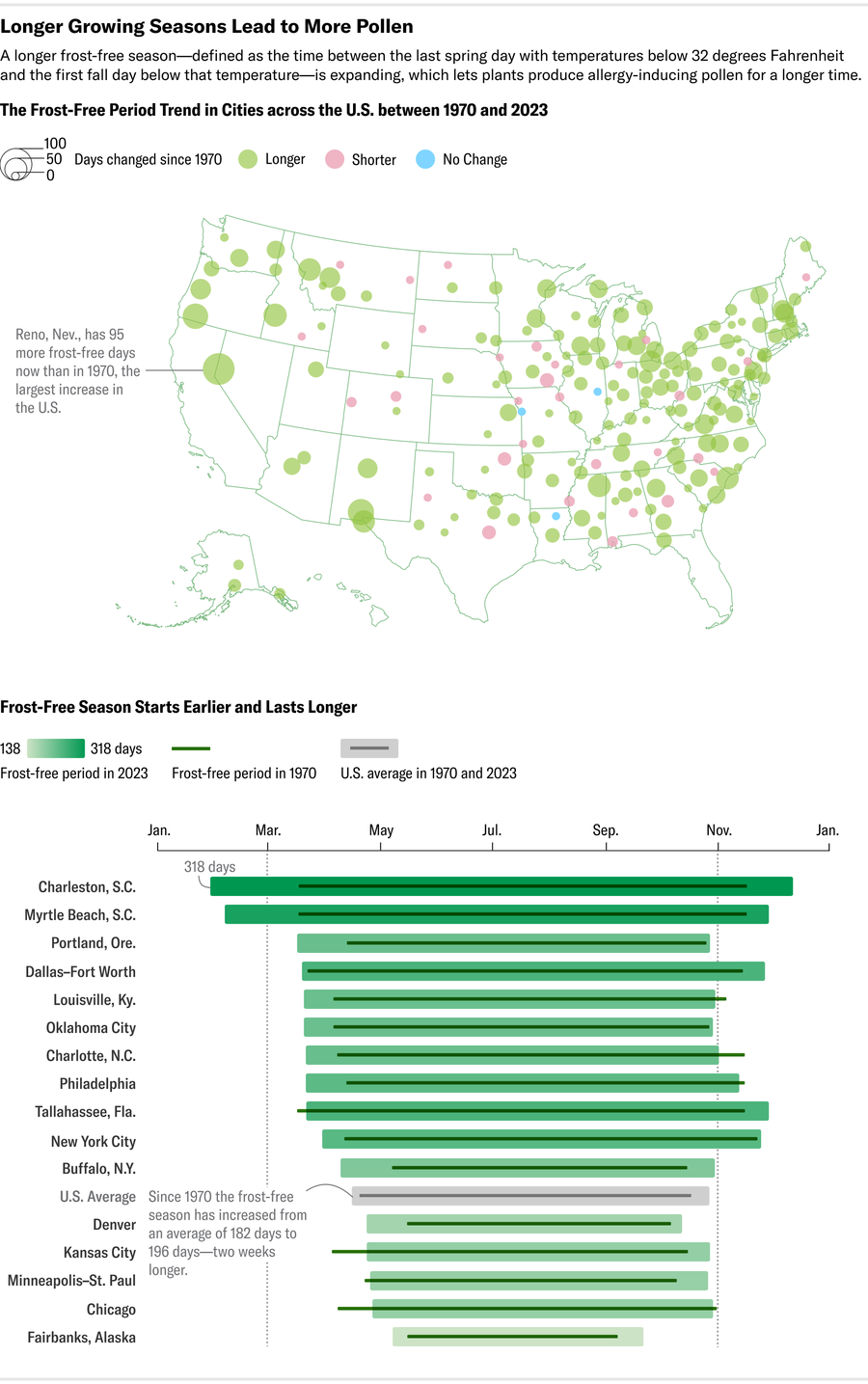

Climate change could be altering U.S. pollen patterns in two ways. The first is by lengthening the country’s “frost-free” season, the period between the final 32-degree-Fahrenheit reading of the year in the spring and the first 32-degree-F reading in the fall. During this time, plants are able to produce blossoms and sprouts without risk of frost damage and can welcome honeybees and other pollinators to collect nectar and distribute pollen. The frost-free season has increased by more than two weeks on average in the contiguous U.S. since the beginning of the 20th century—most notably in the western U.S. And since the 1970s the season has expanded by an average of at least 11 days in all nine of the country’s distinct climate regions. This gives plants more time to produce pollen, thus subjecting pollen-sensitive people to symptoms such as a runny nose and itchy eyes that start sooner and end later in the year.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Credit: Shuyao Xiao; Source: Climate Central (data)

Increasing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is also ramping up the amount of pollen plants produce and thus the country’s average pollen count (the amount per cubic meter in the air in a 24-hour period). This largely has to do with how plants’ male sex organs, which produce pollen, react to carbon dioxide exposure. With high concentrations of this gas in the Earth’s atmosphere, plants can afford to use less energy to pull in carbon dioxide for photosynthesis; instead they invest that energy in producing more pollen. Between 1990 and 2018 pollen concentrations increased by an average of 21 percent across the U.S. and Canada.

For people experiencing worse and longer allergy symptoms, it may be time to reexamine allergy medication type and dosage, Tummala says. “There are many different effective ways of treating allergies from a pharmacologic standpoint. The big ones are oral allergy medications, like Claritin, Allegra [and] Zyrtec,” she says. “But there are also nasal sprays that can easily be used to help ease symptoms in your sinuses.”

Finding the right treatment, or the best combination of them, isn’t always a quick matter. “What works for one person might not work for another, so trying several on with different doses and at different times of the day is the best way to figure out what’s best for you,” Tummala says. She adds that many people can safely use multiple types of medication at once—as long as they strictly follow the instructions on the packaging.

Seasonal allergies can also exacerbate preexisting conditions such as asthma or lead to more acute illnesses—especially in children, says Payel Gupta, an allergy, asthma and immunology specialist at Mount Sinai Medical Center. Prolonged allergic rhinitis can trigger severe eczema and respiratory problems such as chronic sinusitis and asthma attacks. “At my clinic we have definitely observed an increase in people who need help with seasonal allergy symptoms and some who are experiencing even more severe symptoms,” Gupta says. “And as seasons get longer and stronger [from] climate change, I see this trend only continuing to increase.”

In addition to taking medication, people can limit their exposure to allergens by wearing masks, showering regularly, using a neti pot and changing clothes after coming indoors.

But the best long-term way people can protect themselves against the growing pollen plague, Tummala says, is by engaging in climate advocacy and sharing the ways that climate change disproportionately harms people with preexisting respiratory illnesses—especially low-income people of color. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, people in these populations are more likely to have asthma, and to be regularly exposed to other ambient air pollution, than their white counterparts. “From a quality-of-life standpoint, pollen allergies can have a huge negative impact on people and the wallet,” Tummala says. “And this is just one of the many issues with climate change.”

Editor’s Note (4/22/24): This article was edited after posting to better clarify Neelima Tummala’s comments.