What do Beowulf, Batman and Barbie all have in common? Many ancient legends, comic book sagas and blockbuster movies share a storytelling blueprint called the hero's journey. This timeless narrative structure, first described by mythologist Joseph Campbell in 1949, is found in ancient epics, such as the Odyssey and the Epic of Gilgamesh, and modern favorites, including the Harry Potter, Star Wars and Lord of the Rings series. Many such stories have become cultural touchstones that influence how people think about their world and themselves.

Our research reveals that the hero's journey is not just for legends and superheroes. In a recent study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, we show that people who frame their own life as a hero's journey find more significance in it. This insight led us to develop a “restorying” intervention to enrich individuals' sense of meaning and well-being. When people start to see their own lives as heroic quests, we discovered, they report less depression and can cope better with challenges.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The human brain seems hardwired to make sense of the world through stories. Over millennia of evolution, Homo sapiens has spent countless hours sitting around fires and telling tales of challenge and triumph. Our interest in storytelling explains why we read magazine articles that open with an anecdote and why we naturally frame our lives in story form. These life tales stitch together different events into an overarching narrative with the storyteller as the protagonist. They help people define themselves and make existence more coherent.

Of course, some stories are better than others—some evoke awe and excitement, whereas others make people yawn. We wondered whether the hero's journey provides a template for telling a more compelling version of one's own history. After all, the hero's journey lies at the heart of the most culturally significant stories around the world.

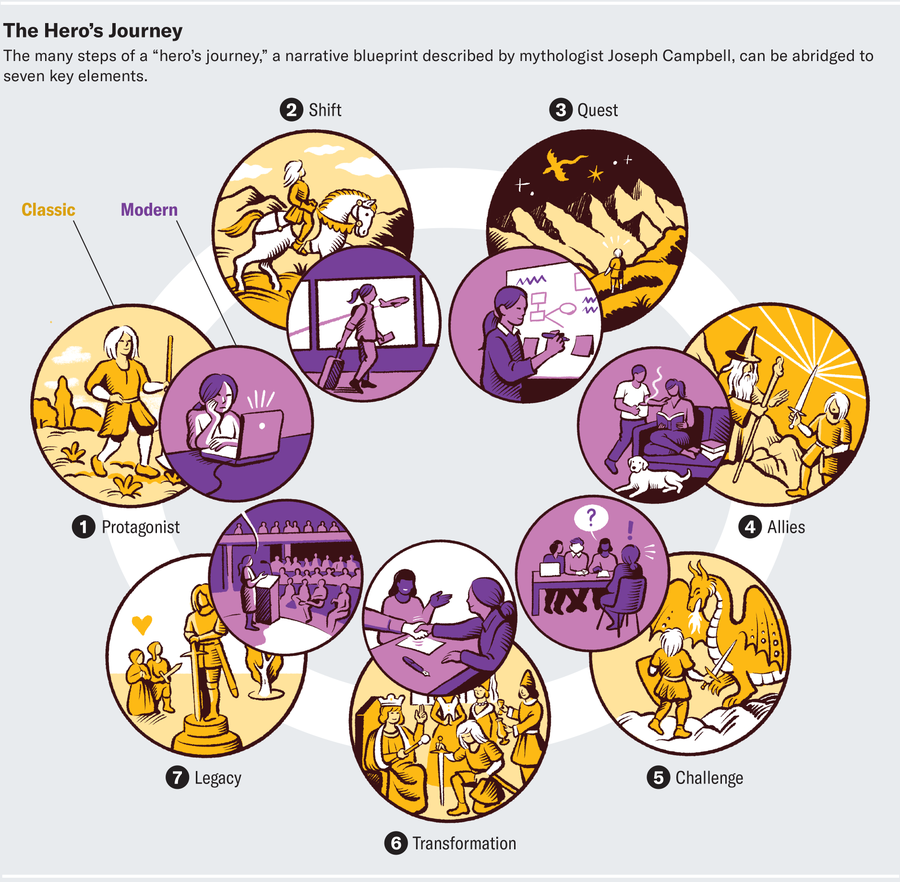

To explore the connection between people's life stories and the hero's journey, we first had to simplify the storytelling arc from Campbell's original formulation, which features 17 steps. Some of the steps in the original set are very specific, such as undertaking a “magic flight” after completing a quest. Think of Dorothy, in the novel The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, being carried by flying monkeys to the Emerald City after vanquishing the Wicked Witch of the West. Others are out of touch with contemporary culture, such as encountering “women as temptresses.” We abridged and condensed the 17 steps into seven elements that can be found in both legends and everyday life: a lead protagonist, a shift of circumstances, a quest, allies, a challenge, a personal transformation and a resulting legacy.

For example, in J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings, Frodo (the protagonist) leaves his home in the Shire (a shift) to destroy the Ring (a quest). Sam and Gandalf (his allies) help him face the enemy forces of Sauron (a challenge). He discovers unexpected inner strength (a transformation) and eventually returns home to help the friends he left behind (a legacy). In an everyday-life parallel, a young woman (the protagonist) might move to Los Angeles (a shift), develop an idea for a new business (a quest), get support from her family and friends (her allies), overcome self-doubt after initial failure (a challenge), grow into a confident and successful leader (a transformation), and ultimately help her community (a legacy).

With our condensed version of the hero's journey, we looked at the connection between how people told their life stories and their feelings of meaning in life. Across four separate studies, we collected life stories from more than 1,200 people, including online participants and a group of middle-aged adults in Chicago. We also used questionnaires to measure the participants' sense of meaning in life, amount of life satisfaction and level of depression.

We then examined their stories for the seven elements of the hero's journey. We found that people who had more of the elements in their life stories reported more meaning in life, more flourishing and less depression. These “heroic” people (men and women were equally likely to see their life as a hero's journey) reported a clearer sense of self than other participants did, as well as more new adventures, strong goals, good friends, and so on.

We also found that narratives in line with the hero's journey provided more benefits than other kinds, including a basic “redemptive” arc, in which a person's life story goes from defeat to triumph. Of course, redemption is often a part of the “transformation” aspect of the hero's journey, but compared with people whose life story contained only the redemptive narrative, those with a full hero's journey reported more meaning in life.

We then wondered whether making one's story more “heroic” would increase feelings of meaningfulness. We developed a “restorying” intervention in which we prompted people to retell their story as a hero's journey. Participants identified each of the seven elements in their life, and then we encouraged them to weave these pieces together into a coherent narrative.

In six studies with more than 1,700 participants, we confirmed that this restorying intervention worked: it helped people see their life as a hero's journey, which in turn made that life feel more meaningful. Intervention recipients also reported greater well-being and became more resilient in the face of personal challenges; these participants saw obstacles more positively and dealt with them more creatively.

Critically, our intervention required two steps: identifying the seven elements and connecting them in a coherent story. In other studies, we found that doing only one or the other—such as describing aspects of one's life that resembled the hero's journey without linking them together—had a much more modest effect on feelings of meaning in life than doing both.

Furthermore, the intervention increased participants' tendency to perceive more meaning in general. For instance, after retelling their stories according to our prompts, people were more likely to perceive patterns in seemingly random strings of letters on a computer screen.

Anyone can frame their life as a hero's journey—and we suspect that people can also benefit from taking small steps toward a more heroic life. You can see yourself as a heroic protagonist, for example, by identifying your values and keeping them top of mind in your day-to-day. You can lean into friendships and new experiences. You can set goals much like those of classic quests to stay motivated and challenge yourself to improve your skills. You can also take stock of lessons learned and ways you might leave a positive legacy for your community or loved ones.

Although you might never save the world on a massive scale, you could save yourself. You can become a hero in the context of your own life, which, at the very least, will make for a better story.

Are you a scientist who specializes in neuroscience, cognitive science or psychology? And have you read a recent peer-reviewed paper that you would like to write about for Mind Matters? Please send suggestions to Scientific American’s Mind Matters editor Daisy Yuhas at pitchmindmatters@gmail.com.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.