New drugs that spur weight loss and treat diabetes have been taking the public—and the pharmaceutical industry—by storm. The latest entrant, Zepbound, recently joined Ozempic, Wegovy, Victoza and others in a growing class of drugs called GLP-1 receptor agonists. With about half a dozen drugs to choose from now and more in development, many doctors say these medications are revolutionizing treatment of obesity, type 2 diabetes and other metabolic diseases.

But keeping the options straight can be a challenge. Though the new drugs may tout similar end results and side effects, doctors say different ones may be most appropriate for different people. Scientific American spoke to experts to help sort through the drugs that are available or on the horizon.

The Origins of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The human gut naturally produces a hormone called GLP-1 in response to eating. When GLP-1 binds to specific receptors in the body, it triggers a series of mechanisms that regulate blood sugar levels, slow the movement of food through the digestive system and act on neurons in the brain—all of which give people a feeling of fullness that helps them eat less and lose weight.

Natural human GLP-1 breaks down quickly in the body, and its effects are short-lived. In the 1990s drug companies began trying to develop a longer-lasting version to treat diabetes. In 2005 a synthetic version called exenatide—inspired by a more stable compound found in Gila monster venom—became the first GLP-1 receptor agonist to be approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

In pharmacology, a receptor agonist mimics another substance, such as a hormone, by binding to its receptor. Scientists have continued to build on the first GLP-1 receptor agonist, producing versions that are more effective and convenient to administer. Some even show promising signs of treating other illnesses, such as heart disease and alcohol addiction.

Liraglutide and Dulaglutide: the Oldest Generation

Exenatide is now rarely used, and two other drugs, called liraglutide and dulaglutide, are now two of the oldest GLP-1 receptor agonists in common circulation. Both were first approved for treating type 2 diabetes. Liraglutide is sold as the weight-loss drug Saxenda and as the diabetes medication Victoza, while dulaglutide is sold as Trulicity, which is only approved for diabetes.

Neither medication manages blood sugar or weight to the same degree as newer versions, but these older drugs are still good options for people with mild diabetes who are not overweight, says Sue Pedersen, an endocrinologist and obesity medicine specialist at the C-endo diabetes and endocrinology clinic in Alberta. “I don’t want them to lose a whole bunch of weight,” she says.

Both liraglutide and dulaglutide must be taken as regular injections—liraglutide daily and dulaglutide weekly. Their molecular structures differ from each other, but “there really are not major differences in their effects on glucose control and body weight,” says endocrinologist Daniel Drucker of the University of Toronto.

Semaglutide: Beginning a New Era

The first generation of GLP-1 receptor agonists achieved less than 10 percent weight loss on average. Newer medications can help people lose around 15 percent of their body weight, says endocrinologist and diabetes researcher Dimitris Papamargaritis of the University of Leicester in England.

That step up came with the FDA approval of a new GLP-1 receptor agonist called semaglutide, best known as a weekly injection to treat type 2 diabetes that is sold under the brand name Ozempic. The drug was first approved for that purpose in 2017 and was then approved as a type 2 diabetes pill called Rybelsus and, most recently, as an injection to treat obesity called Wegovy.

Semaglutide showed a “modest but significant advantage” over dulaglutide for controlling diabetes and enhancing weight loss, Drucker says. It’s not yet clear which aspects of semaglutide give the molecule this advantage. Drucker suspects, however, that it has to do with semaglutide’s ability to circulate longer in the body without degrading, possibly combined with an ability to bind to the GLP-1 receptor more strongly than older drugs.

Semaglutide is also the first (and so far only) GLP-1 receptor agonist shown to decrease the risk of heart attacks and strokes among people who don’t have diabetes, “so that’s a game changer in the landscape of obesity medicine,” Pedersen says.

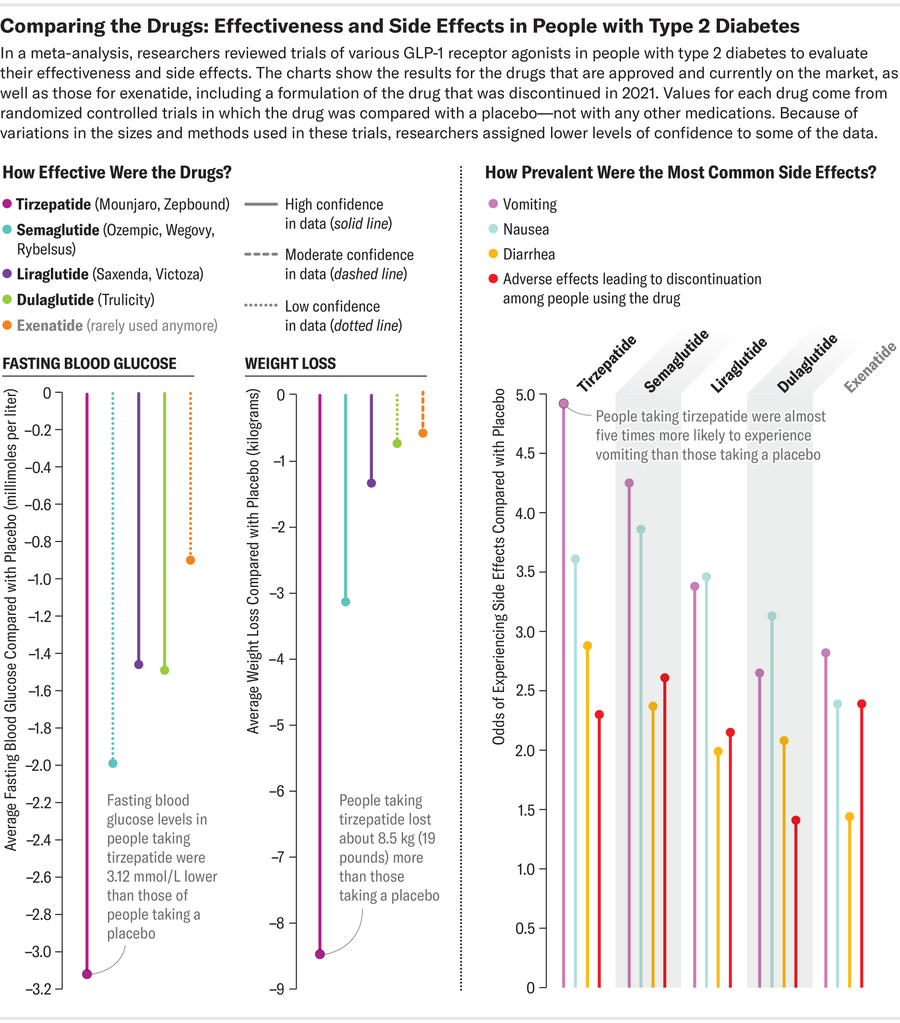

Credit: Amanda Montañez; Source: “Comparative Effectiveness of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists on Glycaemic Control, Body Weight, and Lipid Profile for Type 2 Diabetes: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis,” by Haiqiang Yao et al., in BMJ, Vol. 384, Article No. e076410. Published online January 29, 2024

Tirzepatide: a Two-Pronged Attack

A new player called tirzepatide joined the GLP-1 receptor agonist game in 2022. This drug was first approved for treating type 2 diabetes under the name Mounjaro, and late last year it was approved for weight loss as Zepbound. Tirzepatide is the first agonist to interact with a second receptor, called glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide, or GIP, which affects insulin levels and blood sugar similarly to GLP-1.

This dual action likely allows tirzepatide to control blood sugar better than its predecessors. Clinical trials show the drug can help people lose 20 percent or more of their body mass—more than any previously approved agonists. Researchers are still investigating several hypotheses for why tirzepatide is so effective for weight loss. The drug’s interaction with GIP might underlie the impressive results, or it may activate a different pathway than natural GLP-1 when it is bound to the GLP-1 receptor, Papamargaritis says.

Tirzepatide has not yet been shown to reduce the risk of heart attack or stroke, but studies on this are underway. Despite the drug’s efficacy for diabetes management and weight loss, Pedersen says that, for now, she’d likely recommend a different GLP-1 receptor agonist for people with diabetes or obesity who also have a high risk of heart disease. She adds that new cardiovascular data for tirzepatide could change her mind, however. “That’s all very rapidly evolving,” Pedersen says.

But tirzepatide’s success may come with a downside. “I think there is a trade-off between efficacy and side effects,” says pharmacologist Jin-Yi Wan of the Beijing University of Chinese Medicine. She and her colleagues performed a recent meta-analysis on past, current and prototype GLP-1 receptor agonists, comparing rates of three common side-effects: diarrhea, nausea and vomiting. Their work suggests that semaglutide and tirzepatide—which show greater ability to control blood sugar and body weight than liraglutide and dulaglutide—may also come with slightly higher odds of unpleasant symptoms.

Others aren’t sure side effects deter individuals so drastically, however. For example, the likelihood that someone will stop taking tirzepatide or semaglutide because of their side effects is “pretty similar,” Papamargaritis says, adding that people tend to stick with both drugs at approximately equal rates.

Pedersen’s patients usually find the side effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists to be mild and manageable, she says—but some people can’t tolerate these drugs at all. And they should be used cautiously in people with other certain other conditions, such as retinal diseases, which can be worsened if blood sugar decreases too quickly, Papamargaritis says. Even though GLP-1 receptor agonists are exciting, Pedersen hopes to one day see additional new classes of drugs “so that we can help those patients who just don’t tolerate the GLP-1.”

Options Grow despite Short Supplies

Companies are rapidly working on the next improved GLP-1 receptor agonist. Of the dozens under development, Drucker says two have especially high potential to “move the needle.” The first, called retatrutide, is being developed by the same manufacturer as tirzepatide and would be the first to interact with a third receptor in addition to GLP-1 and GIP. Like the GLP-1 receptor, this third target, the glucagon receptor, regulates blood sugar and may also influence food intake and fat storage. The second, CagriSema, combines semaglutide with a synthetic version of a hormone called amylin that also promotes fullness. Early tests suggest both can produce even better glucose control and weight loss than the current options. “That will be fantastic for patients,” Drucker says.

More options could help fill gaps in access. High prices have put GLP-1 receptor agonists out of reach for many people, especially in low-income countries. Manufacturer list prices are around $900 or more (and retail prices even higher) for about a month’s supply of any of the GLP-1 agonists that are widely used in the U.S. Insurance companies are more likely to cover the drugs if they’re used to treat diabetes than if they’re used for weight loss—a frustration for people without diabetes who seek the benefits of weight loss.

It’s difficult to prescribe a less effective drug while “knowing that there’s something better out there,” says Yasmin Mesquita, a medical student and researcher at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro in Brazil. Supply shortages have also frustrated some people. In the U.K., health authorities have asked doctors not to start additional patients on semaglutide because of limited supplies, Papamargaritis says. Wan worries shortages may prompt consumers to turn to online vendors and take these drugs without a doctor’s guidance.

Beyond weight loss and diabetes, researchers are also investigating a growing list of conditions GLP-1 agonists could help treat. For example, recent publications suggest these drugs tone down overactive immune reactions in the brain, a process that could help treat neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s.

“It’s really, I think, a very bright future for this area of medicine,” Drucker says.