Imagine being pregnant and looking forward to becoming a parent. However, during a routine diagnostic test, your doctor tells you your pregnancy isn’t viable; at birth, your baby will likely not survive long outside the womb. Because you live in a state like Texas that has recently banned abortion with few exceptions, you now need to carry this pregnancy to term, carrying the grief of a non-viable fetus and likely endangering your own life in the process.

If you lived somewhere else, you might have had the option to terminate the pregnancy in-state, right away. Instead you have to endure the physical and emotional agony of childbirth, only to hold your newborn as they pass away in your arms, or to take that child home and care for them until they die—all because your state government has stripped you of your right to make a deeply personal decision in consultation with your doctor.

As mothers with children ranging in age from nine months to nine years, we vividly recall the anxiety surrounding pregnancy and the early months of parenting an infant: waiting for test results to know whether we are healthy, whether our baby is healthy. At times, we were overwhelmed with anxiety that, at any point in those early days, the worst could happen. So many new and expecting parents live with these feelings. Pregnancy is hard enough. Parenting is daunting. But, when your state government forces you to continue a doomed pregnancy, the grief is unfathomable.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

These laws, these “heartbeat bills” and sweeping abortion bans that have so few exceptions, are inhumane. Our research on infant mortality in Texas after the passage of such a bill shows that these laws endanger maternal and infant health. We have to fight back. Health, bodily autonomy and the right to not needlessly suffer as a pregnant person are what’s important here, not the ideological claims of people who view a fetus’s rights as more important than those of the living, breathing person who carries one.

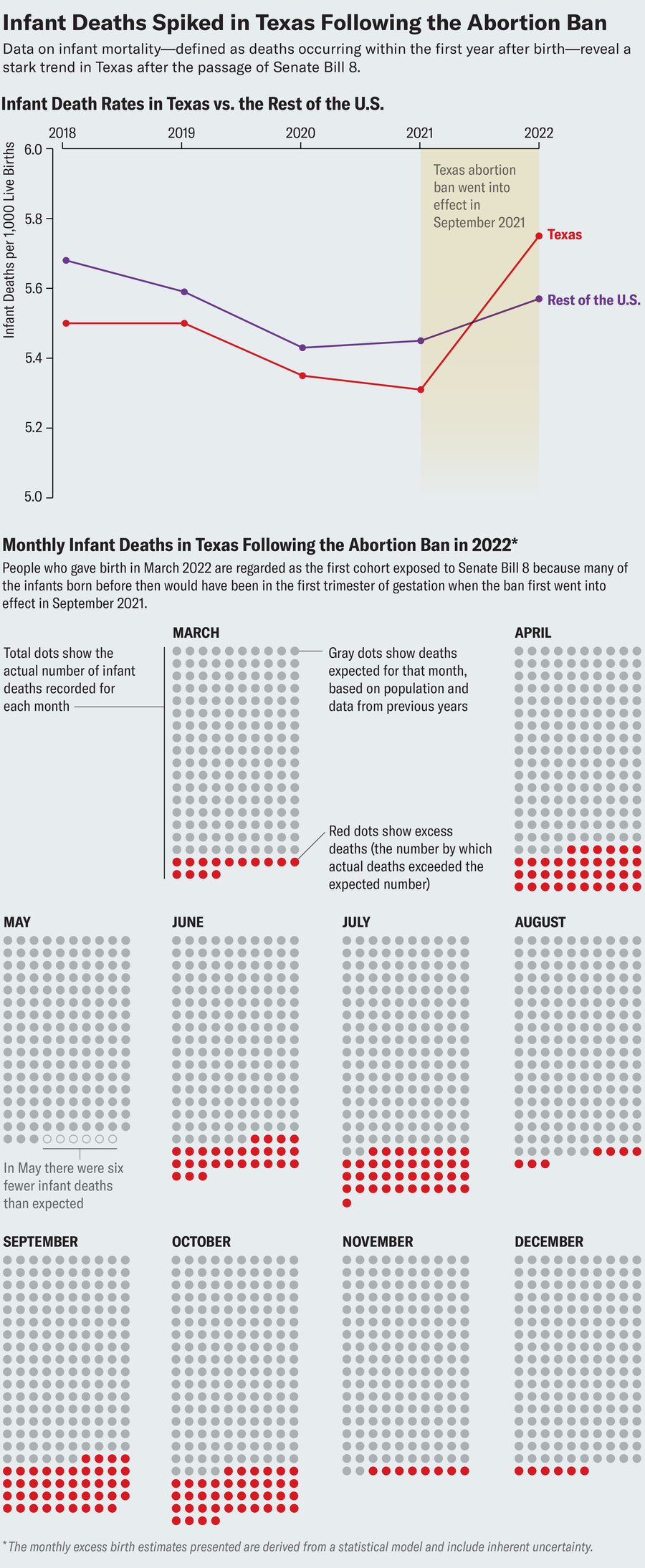

Texas was among the first states to pass a heartbeat bill, prohibiting abortions as early as five weeks’ gestation, the time when the electrical impulses that we associate with heart formation begin. We found that, in Texas, infant mortality—including deaths in the first year of life—increased by 13 percent between 2021 and 2022 following the passage of this bill, while infant mortality increased by only 2 percent in all other U.S. states.

It's worth noting that infant mortality in Texas is a serious problem—nearly six of every 1,000 live births end in a death in the first year. The states with the lowest rates are between three and four per 1,000, which may not seem like a large difference but would translate to hundreds of fewer deaths in Texas annually.

In Texas the leading cause for this increase in infant mortality appears to be deaths from birth defects, which rose 23 percent in Texas after the passage of Senate Bill 8, while declining 3 percent in all other states. What’s more, deaths in Texas caused by accidents increased by 21 percent and those that resulted from maternal complications in pregnancy increased by 18 percent; the corresponding increases in the rest of the U.S. were much lower at 1 percent and 8 percent, respectively.

Abortion bans cause these spillover effects. These bans disregard medical reality and the inherent complexity surrounding pregnancy. Policies that try to legislate pregnancy result in needless suffering, as Kate Cox’s legal case makes clear. Because of Texas’s ban, this mother of two who had a nonviable pregnancy had to travel out of state for routine medical care—after suing for the right to be treated in her home state.

In contrast, one colleague of ours shared that, in the spring of 2022, she had a concerning fetal scan when she was 16 weeks pregnant. Her ob-gyn told her, “You live in Maryland, so you’ll have options.” Having the option to terminate a pregnancy without traveling hundreds of miles should not be state dependent.

We need policies that respect the nuanced and individualized nature of pregnancy, ensuring that medical decisions are made by people, their doctors and, where applicable, their prenatal counselors—not dictated by politicians or judges. Making exceptions to abortion bans for certain scenarios is inadequate; pregnancy is inherently dangerous, and the law is incapable of parsing all the ways in which a pregnancy can go wrong.

Since our publication and the proliferation of heartbreaking anecdotes that magnify these negative effects, we have seen the pro-life movement treat people’s traumatic experiences as collateral damage for the larger cause of saving fetuses. For many who oppose abortion, these tragic outcomes are viewed as unfortunate but necessary sacrifices for the mission to prevent abortion at all costs. This approach treats the health of pregnant people as secondary to the fetus, which is unacceptable.

What we’re talking about isn’t rare. The odds are high that you know someone who has either experienced the heartbreak of a congenital fetal diagnosis or obtained an abortion. Approximately 3 percent of babies in the U.S. have birth defects. That means numerous pregnancies involve serious congenital abnormalities, and thousands of families each year have to grapple with a pregnancy that will not yield a healthy child who will live.

As public health researchers, mothers and Americans, we recognize the urgency of this subject. Our research tells us that repealing abortion bans and protecting the right to make decisions about one’s pregnancy are critical. It is also what most Americans want: 63 percent of people support the right to abortion in most or all circumstances, which has increased four percentage points since before the Supreme Court’s 2022 decision in the Dobbs case.

Our work underscores that lawmakers must put women, people who can become pregnant, and children over political agendas. In the 13 states with upcoming ballot measures that would enshrine the right to abortion in the state constitution, voters have the opportunity to bypass lawmakers and prevent further harms from abortion bans. And people in many other states can vote for candidates who uphold pregnant people’s bodily autonomy and right to choose, no matter what.

The stakes couldn't be higher: if we fail to act, we institutionalize needless pain and suffering for the more than 50 percent of the population who could become pregnant in their lifetime, and the people who love them.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.