Are you an “ISFP” like Bob Dylan and Rihanna or an “ENTJ” like Bill Gates and Margaret Thatcher? Perhaps you’re an “INTP” like Albert Einstein and Tina Fey? If you are one of tens of millions of people who have taken a Myers-Briggs personality test—a staple of business schools and online quizzes—you know the answer. But are these personality categories meaningful or just a bunch of nonsense?

Developed during World War II, the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, as it is formally known, or MBTI, is likely the most popular personality test in the world. It purports to break the populace down into 16 categories based on four personality dimensions: extraversion (E) or introversion (I), which measures whether you get energy from outwardly focused action like socializing or from inwardly focused activities like quiet reflection; intuition (N) or sensing (S), which measures how much you see big picture patterns rather than focusing on sensory information from direct experience; thinking (T) or feeling (F), which measures whether you make decisions using logic rather than by focusing on feelings; and judging (J) or perceiving (P), which measures your preference for structure rather than spontaneity.

Sounds great, but there is a dirty secret to these types of tests. They are usually not as useful as proponents claim—and less useful than other personality tests. Take the Big Five personality model, which notably rests on decades of statistical validation by psychologists. That test rates people on five personality traits: conscientiousness, agreeableness, neuroticism, openness to experience and extraversion.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

My colleagues and I decided to compare the two test types. So we investigated an MBTI-style test and a Big Five test to see how well each predicted 37 “life outcomes” in a just released report. (We use the term “MBTI-style” to refer to tests that are modeled on the constructs of MBTI but aren’t official forms of the MBTI test.) These outcomes included important facts about people’s lives, ranging from how many close friends they had to how often they exercised to how satisfied they were with life. To do so, we recruited 559 people in the U.S. using our online Positly study participant recruitment platform.

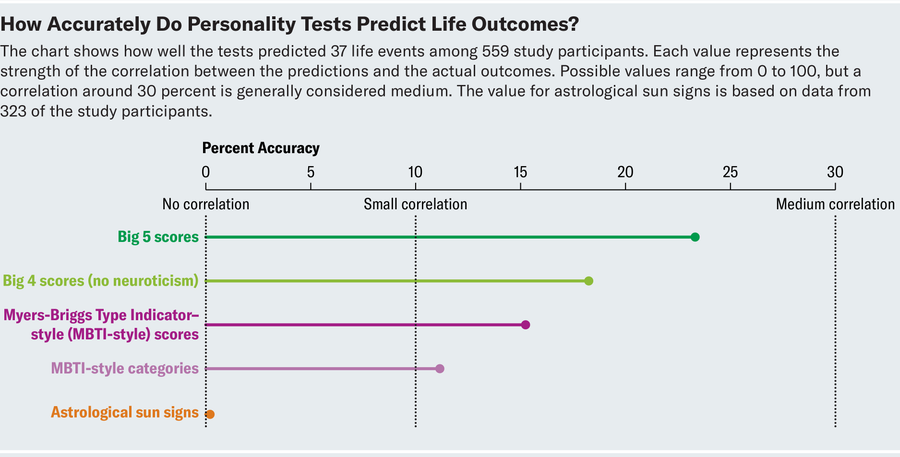

On average, the Big Five test was about twice as accurate as the MBTI-style test for predicting these life outcomes, placing the usefulness of the MBTI-style test halfway between science and astrology—literally. When we tried predicting these same life outcomes using astrological sun signs (e.g., whether someone is a Pisces or Aries), we achieved zero prediction accuracy. In other words, sun sign astrology didn’t appear to work at all for predicting people’s lives. And while the MBTI-style test fared better, it was still often wrong in its predictions. What’s more, adding MBTI-style personality results to Big Five ones didn’t lead to predictions that were any more on the mark than Big Five ones alone. (If you’d like to compare your own Big Five and MBTI-style results to see how accurate they are, you can do so here using a free version of the test that we created as part of our study.)

Why are MBTI-style tests often so much worse than Big Five ones? We found two major reasons.

MBTI-style tests typically measure four of the Big Five personality traits. The tests’ scales for extraversion, intuition and feeling are a decently close match with Big Five’s extraversion, openness to experience and agreeableness, respectively. And in our study the test’s judging dimension represents a mixture of Big Five openness, extraversion and (lack of)conscientiousness.

But MBTI-style tests typically don’t measure neuroticism, which is an important predictor of many crucial life outcomes, such as career success, suicidal thoughts and life satisfaction. Without the trait of neuroticism, our Big Five test’s predictive accuracy fell by 22 percent (the correlation between what we could predict about people from their personality traits and what was really true of those people dropped from 0.23 down to 0.18).

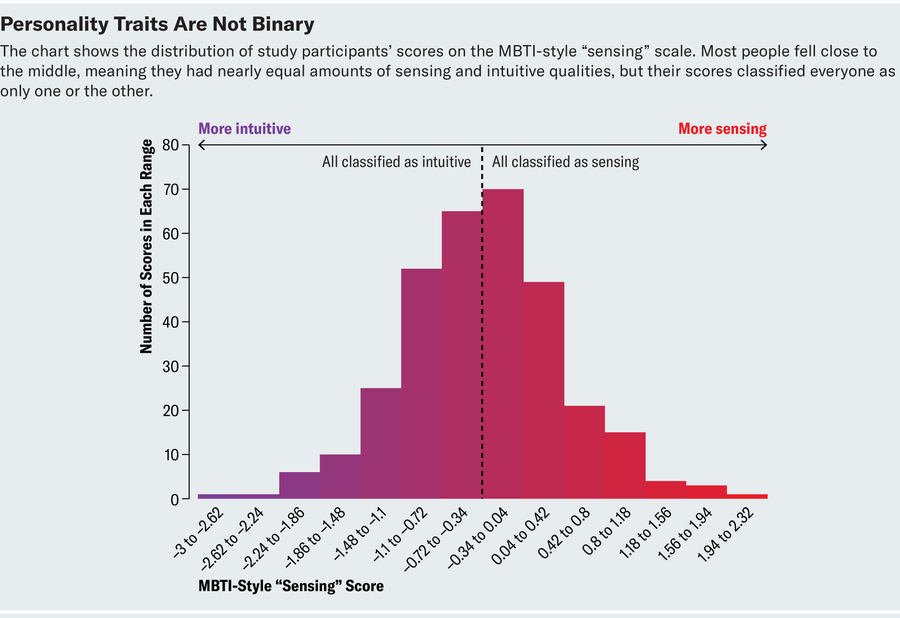

A second problem with MBTI-style tests is that they force people into two distinct categories for each trait. Rather than assigning you a score for each trait (like the Big Five does), they usually report your personality using a letter for each trait, such as E versus I, and S versus N. We found all four of the MBTI-style traits to be close to normally distributed (i.e., shaped like bell curves), however. Most people are far from fully judging or perceptive, extraverted or introverted, thinking or feeling, or sensing or intuitive. They are instead somewhere near the middle. We found the MBTI-style test would be about 38 percent better in predicting major life outcomes if it didn’t dichotomize people’s traits.

So, what accounts for the enduring popularity of MBTI-style tests if they appear to be surpassed by the Big Five in predictive capacity?

For one, they may be less offensive than other tests. After giving 236 people in the U.S. both the MBTI-style test and the Big Five test, we asked them what they thought about the results. When asked if their report made them feel good about their personality, 10 percent disagreed for the MBTI-style report, while 19 percent disagreed for the Big Five. That's nearly double the dissatisfaction, suggesting that the softer framing of the former report was less insulting.

This may be in part because MBTI-style tests give a more positive spin to some of the negative traits in Big Five tests. People who, on the Big Five, are told they are less open to new experiences—which could make them feel bad—are rebranded as “sensing.” Disagreeableness is rebranded as thinking (by merging the trait of “not taking into account other people’s emotions” with the trait of being “logical”). And perhaps the most negative-sounding trait of all—neuroticism—is left out of the whole exercise.

Interestingly, people in our study believed that the MBTI-style results were just as accurate as the Big Five results.

If MBTI-style tests offer little meaningful new information about individuals’ personalities that can’t be found in other tests, they do at least teach us about a widespread trait: the desire to feel good about oneself—and one’s psyche. Our study suggests that MBTI-style tests may be sacrificing predictive accuracy in exchange for gratification. Relative to other options, MBTI-style tests may be worse at telling you whether you will excel at your job, relationship or life. But they can give some cool labels to some of your personality foibles. And that is something just about everybody—from an ENTJ to an ISFP—can rally around.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.