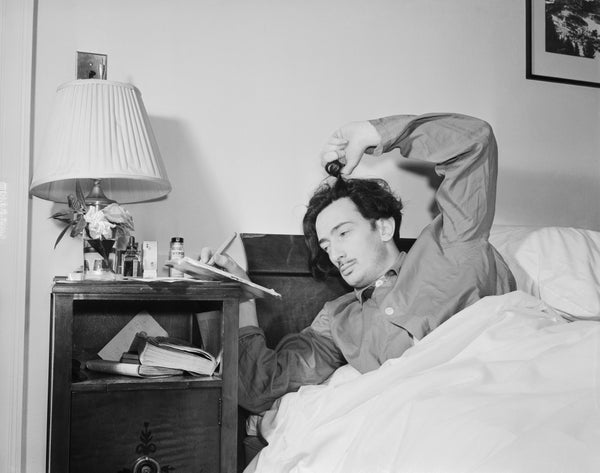

Salvador Dali had a peculiar way of refreshing his mind—something he called “slumber with a key.” In his 1948 book 50 Secrets of Magic Craftsmanship, he described how it worked.

“You must seat yourself in a bony armchair, preferably of Spanish style,” he wrote. In your left hand, you were to clench a heavy key, suspended above a plate. Then, he continued, “you will have merely to let yourself be progressively invaded by a serene afternoon sleep, like the spiritual drop of anisette of your soul rising in the cube of sugar of your body.”

As you drifted off, the key would slip from your fingers and clang on the plate, awakening you. He claimed the brief moment spent between wake and sleep would revive your physical and psychic being. And he cautioned that “a mere second is infinitely too long.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Now Dali’s mystical-sounding method has been, to some degree, vindicated by science.

Delphine Oudiette: We show that this period between wake and sleep is actually very inspiring for creativity—and napping with an object in hand might help to tap into this creative sweet spot.

Christopher Intagliata:Delphine Oudiette is a sleep researcher at the Paris Brain Institute. Since childhood, she’s found it easy to slip into the zone between wake and sleep.

Oudiette: I try to sleep with a problem in mind and let the images come to me. And sometimes I have great ideas.

Intagliata: But she was curious to find out why—so she and her colleagues asked 103 volunteers to complete a series of math problems. Unbeknownst to the participants, there was a quick shortcut to solve all the problems. (Sixteen of the volunteers figured that out and were excluded from the rest of the study.)

The volunteers who didn’t determine the secret were asked to emulate Dali’s method—but pinching a plastic bottle with their fingertips rather than a key. Some took a Dali-style micro nap, some napped longer, and others didn’t nap at all.

After the snooze, the researchers asked all the volunteers to do hundreds more of these math problems. And they found that volunteers who took micro naps were nearly three times as likely to figure out the problem-solving trick, compared to those who didn’t nap at all.

Oudiette: That’s a pretty massive result. We think, maybe in this phase, you have the best of the two worlds: sleep and wake. So you lose control of your thoughts. So you can have loose associations—make distant associations between different memories—and that could be helpful for creativity. But at the same time, you keep some awareness that might help you to recognize when you have a great idea.

Intagliata: Those who slept for longer periods actually did worse than both those who briefly slept and those who stayed awake. The results appear in the journal Science Advances. [Célia Lacaux et al., Sleep onset is a creative sweet spot]

Oudiette says the next step of her work will involve repeating the experiment with other creative tasks, beyond math problems ...

Oudiette: And, yeah, to know more about the mechanism—and maybe to try to teach people to reach this creative sweet spot.

Intagliata: As for Dali? In his book, he describes a variation of his method in which he instructs the reader to, quote, “eat three dozen sea urchins, gathered on one of the last two days that precede the full moon.” He specified that “these sea urchins should be eaten preferably in the spring—May is a good month.”

Clearly, the great painter has left scientists with much to investigate.

[The above text is a transcript of this podcast.]